Book-cover, Courtesy of Gestalten

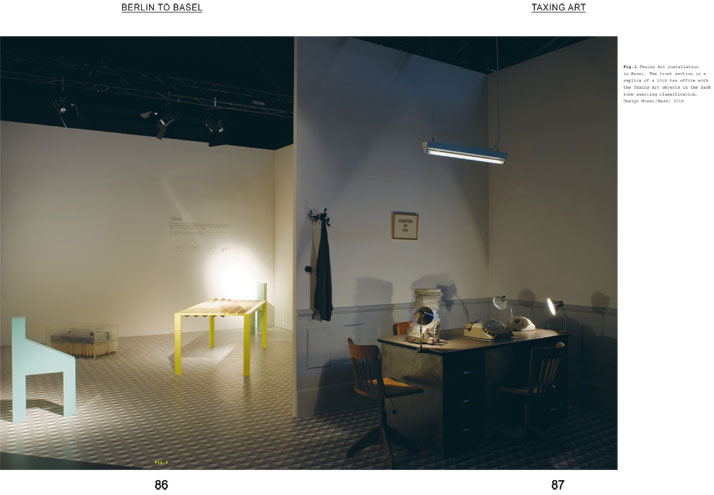

Where does one draw the fine line between art and design, what are the boundaries between the two? Have they been blurred in recent days? Today, it is not the object itself, but rather its economic functionality that determines its category. To our surprise, we discovered through the book Taxing Art: When Objects Travel by Beta Tank, which was published by Gestalten that often custom officials subjectively decide what constitutes art and design based on their personal views and erratic local tax laws! In opposition to this condition, Taxing Art is a buoyantly ironic, case study and documentation of the consequence of conventional, bureaucratic measures on innovative work. Taxing Art puts on the spotlight the largely miscalculated outcome of erratic tax laws and the result they have on the world of art and design.

b-side table, photo © Beta Tank

The experiment was accomplished with one of Beta Tank’s newest objects and the last object from the Taxing Art series, the b-side table, commissioned by Dilmos Gallery, Milan for the Unison exhibition during Milano Salone (April 2011). The b-side table can be seen both as a functional and a non-functional object, but who is to decide whether it should be taxed at 7% or 19% VAT. b-side table is half handmade and half machine made; the handmade part is sculptured in such a way that it is deprived of its functionality thus making it an art object and the other half is a regular coffee table which would be taxed as a design object at 19%. Who is to judge what this object is and how it should be taxed? With what knowledge and with what background do customs officials decide? Five objects were especially made by Beta Tank to travel a 12,000-kilometer journey in response to these rigid rules and regulations as they test the tax laws around the world.

Beta Tank is a Berlin-based conceptual product design practice which was founded by Eyal Burstein. Beta Tank creates objects based on cross-disciplinary research that explores new technologies and social commentary—inspiring debate beyond aesthetics or function, creating stimulating work while carefully studying the sensory substitution concept. Burstein, an Israeli, Berlin-based product designer attended the London College of Printing in London in 2001–2004 and the Royal College of Arts in London from 2004-2006. In 2007 Burstein founded Beta Tank, and in 2008 he exhibited the Design and the Elastic Mind Exhibition at the MoMA in New York, which was curated by Paola Antonelli. In 2010 Beta Tank was awarded Designer of The Future award by Design Miami during the Art Basel. But should we rather let Eyal Burstein speak for himself ? b-side table, photo © Beta Tank

Eye Candy, Yellow, © Beta Tank, 2008

How did the sensory substitution concept in your works come about? What triggered you to start working with this concept? Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

In 2007, a year after I graduated from the RCA, I came across a short BBC video segment about the concept of being able to see images using one’s tongue, as an option for blind people. After seeing the segment I wondered if the ability to see using parts of the body, other than the eyes, could be used by people who are not blind. Using that idea as a starting point, I began to question what such a device would look like and how it would be consumed. In order to create such a device however, I needed to understand more about vision. Thus I began to research about vision, perception, and sensory substitution. (I can no longer find the original video I saw, but this is a related one: ''Blinded Merseyside soldier 'sees' with tongue device''. It speaks about the technology in terms defined by my project, namely the use of the word lollipop to describe the mouth piece. I find it satisfying to see that a company that was unaware of Beta Tank’s project is using the research done by Beta Tank in their own Public Relations.)

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

Mind Chair Polyprop, © Beta Tank + Peter Marigold, 2008

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

Mind Chair Polyprop, © Beta Tank + Peter Marigold, 2008

Have you worked closely with a neuroscientist for these projects, and if so, how easy is it to be creative given the scientific restrictions and having to translate that to everyday design? Mind Chair, Working Prototype, © Beta Tank, 2008

Whilst making prototypes and brainstorming ideas, I came across the work of Dr. Beau Lotto and his Lotto Lab in UCL, London, UK. Dr. Beau Lotto gave Beta Tank a space in his lab and spent a lot of time talking and explaining various ideas. The idea was to understand the science behind vision, rather than work out how to make a product that works. I didn't find that there were any scientific restrictions - on the contrary, every time I come across new ideas, I find science to be more magical and fascinating! It is the unbelievable research that is hard to translate; explaining to people that the mind can see with its back or tongue is the most complicated part. By comparison, translating complex science into everyday objects is quite easy.

When designing do you focus more on function or on the social interaction of an object? Are you inhibited by function vs. social interaction?

In general every aspect of my design process goes to serve my original concept. I’m not sure I focus on either of the above-mentioned things. I have an initial idea, something I find fascinating, and I begin designing objects that are related to that concept. I guess that leans more on the social interaction of the objects, but I don’t find that any of that inhibits me. I feel free and believe that I truly design whatever I want, without consciously thinking about the consequences, whether good or bad.

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

From where do you draw your inspiration?

I draw my inspiration from objects that haven’t been designed, but are incorporated into everyday life. I like to shine a light on issues that are ignored, taken for granted, or accepted by us all. For example, ‘Taxing Art’ became a project the moment I realized that I was censoring myself, or taking tax laws into consideration while I was making my objects. Realizing that the government is in my head was both freighting and inspiring.

What was your first reaction when you found out that your work would be part of the MOMA Collection, at such a young age?

I remember thinking in the beginning that after this exhibition the studio would have less of a struggle, especially when I was told that the MoMA will be buying the works for their permanent collection. However, after Design and The Elastic Mind, it took two years until requests for exhibitions, design fairs and galleries started to become consistent. In fact, 2011 is the first year that has been booked up in advance. So whilst it was a great honor and source of pride to have my work at the MoMA, in reality, it’s not as fast a progression as it may seem.

Pyramid table, © Beta Tank

Nearly a decade from the day you started studying at London College of Printing, did you ever imagine that you would have accomplished so much in such little time? How did you imagine yourself back then, and what do you think has been your greatest achievement within these 10-years?

I remember that I wanted to study graphic design so that I could continue traveling, making fliers and posters along the way in order to fund my travels. At LCP I met an inspiring tutor called Mr. Biggles who studied at the RCA and introduced me to an eccentric and free way of working and thinking. It was Biggles who suggested that I apply to the RCA. So the road to Beta Tank was completely unplanned. In that regard, I am pleased with the amount of work that I have done since the five years I have had my own company and the pace at which I’m going, but I don’t think I have necessarily achieved great things. I have to continue to produce work and keep growing as a designer.

Is there any specific project for which you feel particularly satisfied and proud of?

I am quite satisfied with the eye candy project because it mixed design and science and I managed to get the concepts to be understood and wanted by many different people. I am proud of the book because writing is not exactly my world, but I ended up having fun with it and think the outcome was quite good.

How did the book come about, what triggered you to publish it?

After coming back from Basel I wanted to develop the side of the project that involved taking the objects across borders. This is the part of design that most designers do not deal with. If they do, it's not a particularly a nice part of the designing process. In Basel I drove straight through the border on purpose, in order to create a legal problem once the objects were in Basel, which is explained in the book. From then on I realized that there were plenty more shipping nightmares for me to confront. Although the project started with the aim of revealing the complicated realities of shipping design objects around the world, I still had to ensure that the taxing art objects made the deadlines of the various W Hotel exhibitions. Once W Hotels and I outlined the project, I approached the Gestalten Verlag, hoping that they would want to publish the journey. I met Robert Klanten who runs Gestalten and at the end of the meeting he agreed to publish the book. I had never written a book before and the mammoth task only dawned on me at a much later stage, but somehow I managed to write it and hope it turned out alright.

Galila GelbBeta Tank, 2010, © Beta Tank

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

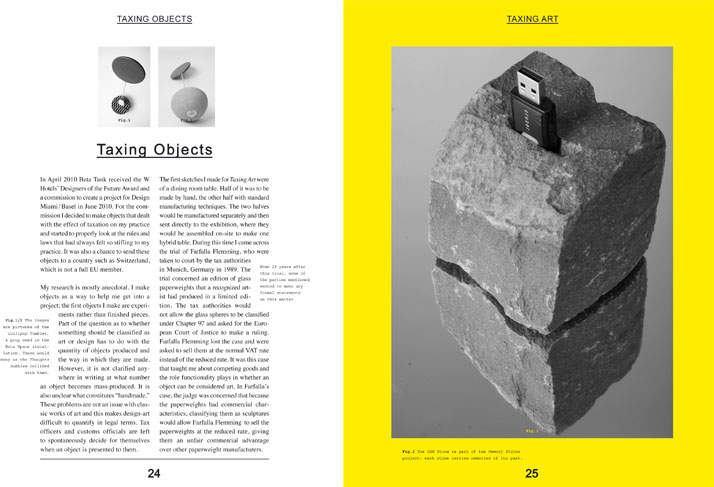

Tell us about ‘Taxing Art’. Memory Stücks - Stone, © Beta Tank, 2009

‘Taxing Art’ is a project about how government policy affects creativity and innovation. I began thinking about it when I moved from London to Berlin. In Berlin, in contrast to the UK, I noticed how close my relationship is to the tax authorities and their agents, including my accountant. It was such a source of friction and frustration that I was determined to understand it more fully. I was working in the exact same way that I was in London, but in Berlin it did not go as smoothly. My accountant would call me up to discuss expenses in such a way, that I slowly realized I could preempt what my accountant would ask me, and would therefore try to avoid those issues while designing. At one point I remember speaking to my accountant about a pitch I made for a Camper store in Berlin where a pair of shoes was bought as part of the service design analysis. The accountant ended up booking the shoes as an owner’s loan of the shoes to Beta Tank because I could not prove that they would never be used outside the office. This is explained further in the book, but in general I found all of these instances amazing and worth pursuing.

Memory Stücks - Stone, © Beta Tank, 2009

What is the day like in the life of Eyal Burstein?

The days when I am not preparing for shows I can wake up around 10am, go to my coffee shop, answer emails and think. When the weather is nice I like to bike around the city. In the evenings I am either relaxing at home or at an art of design event, I sometimes go to a bar.

I live in the center of town and mostly enjoy the relaxed life that seems only to be possible in a city like Berlin. There is very little separation between my work and my life, except for my girlfriend, with whom I live, and occasional holidays. I am very grateful for the lack of distinction between my work and life. It enables me to work from everywhere and to set my own schedule. I work from my laptop, usually in a coffee shop near my house. I do not have a workshop, many tools or employees, which keeps me very light and agile. I have a storage place where objects come in and out, but this can also happen without my physical presence. In Berlin I have a network of professionals who I work with to produce and ship things around the world.

When I’m getting ready for shows and events, things are more manic and I often find myself working a few days straight with very little sleep. This is when not having a studio can be frustrating, as I rely on three or four different companies to coordinate with and complete things on time. (This is not simple when you don't speak the language :) ) Book-spread, Courtesy of Gestalten

What are your future plans?

I would love to carry on doing more of the same things. I’m off to Basel on the 13th of June, which is where it all started, and I very much look forward to this. After Basel I’m touring Asia, which will mark the start of my next project. On the 17th of September, 2011 I will be showing my findings at the Victoria and Albert Museum as part of the London Design Festival. Later that month I will be showing work at the Cheongju International Craft Biennale 2011 in Korea. Finally, after this I will go to Design Miami Basel. At the moment I am not showing any work there, but it's the most fun design fair I’ve ever been to.

Memory Stücks - table, stone, Barometer and Iron, © Beta Tank, 2009

2 June - 3 July, 2011:

Visit the Beta Tank exhibition at the Gestalten Space in Berlin.