Porky Hefer Finds Inspiration in Bird Nests for his Immersive Desert Retreat in Namibia

Words by Eric David

Location

Namib Tsaris Conservancy, Namibia

Porky Hefer Finds Inspiration in Bird Nests for his Immersive Desert Retreat in Namibia

Words by Eric David

Namib Tsaris Conservancy, Namibia

Namib Tsaris Conservancy, Namibia

Location

For South African designer Porky Hefer, architects and designers have much to learn from nature, in particular nests which have been inspiring the sculptural seating pods he is known for. But whereas nests are pragmatic and functional, Hefer’s designs are imaginative and daring, his goal being to “entertain the imagination” as he explained to Yatzer, which, judging from his first architectural project – an off the grid, hand-crafted retreat in a remote valley of the Namib Desert in Namibia – he is extremely successful at.

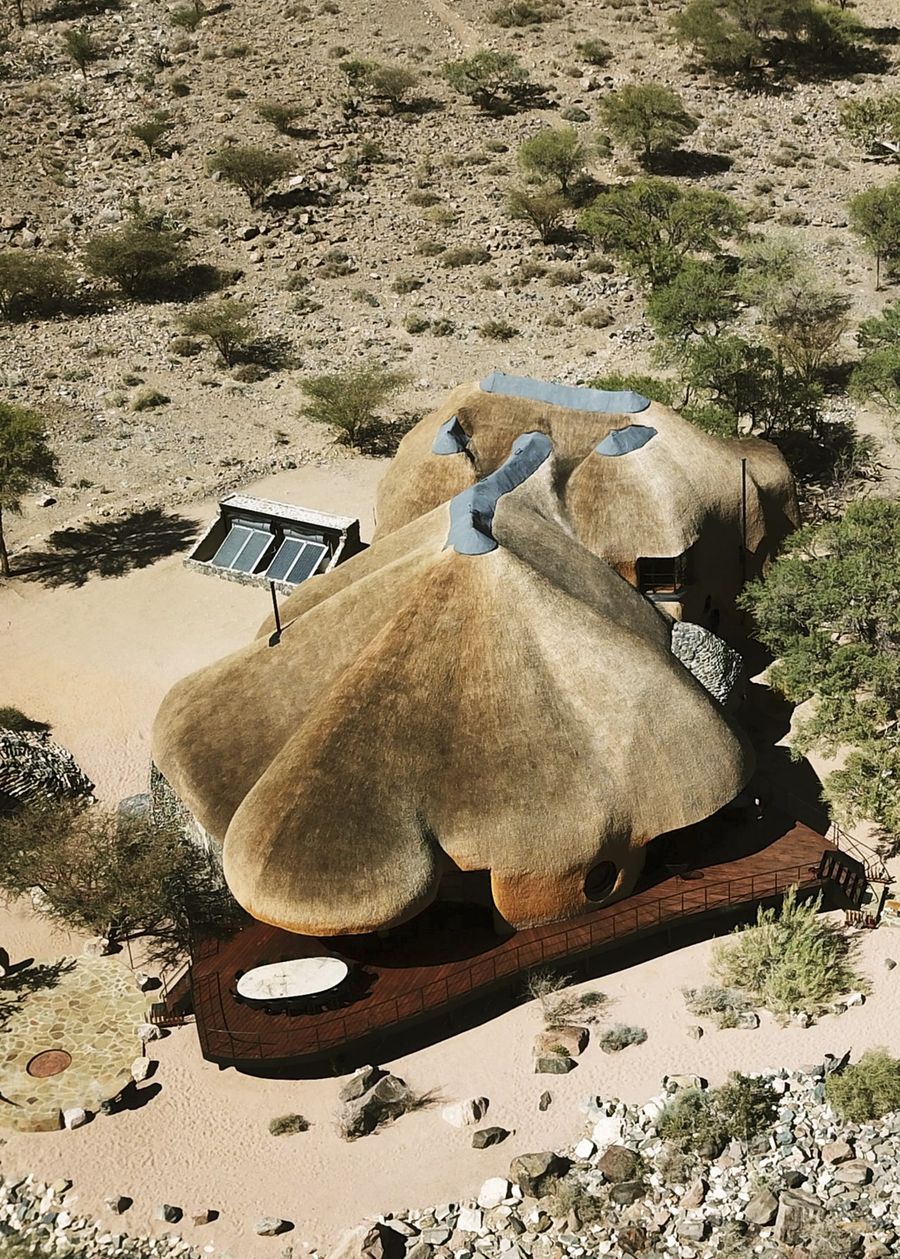

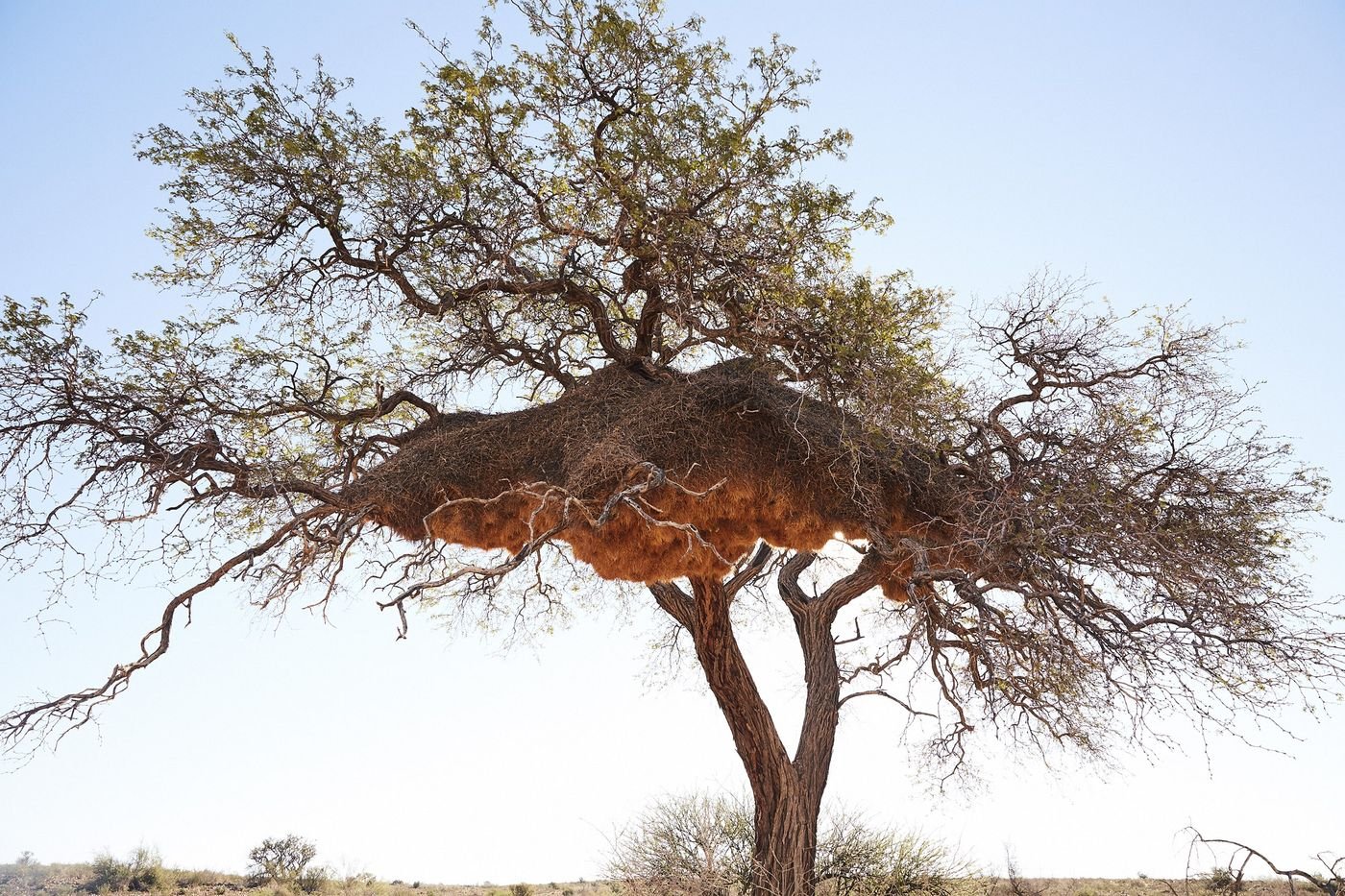

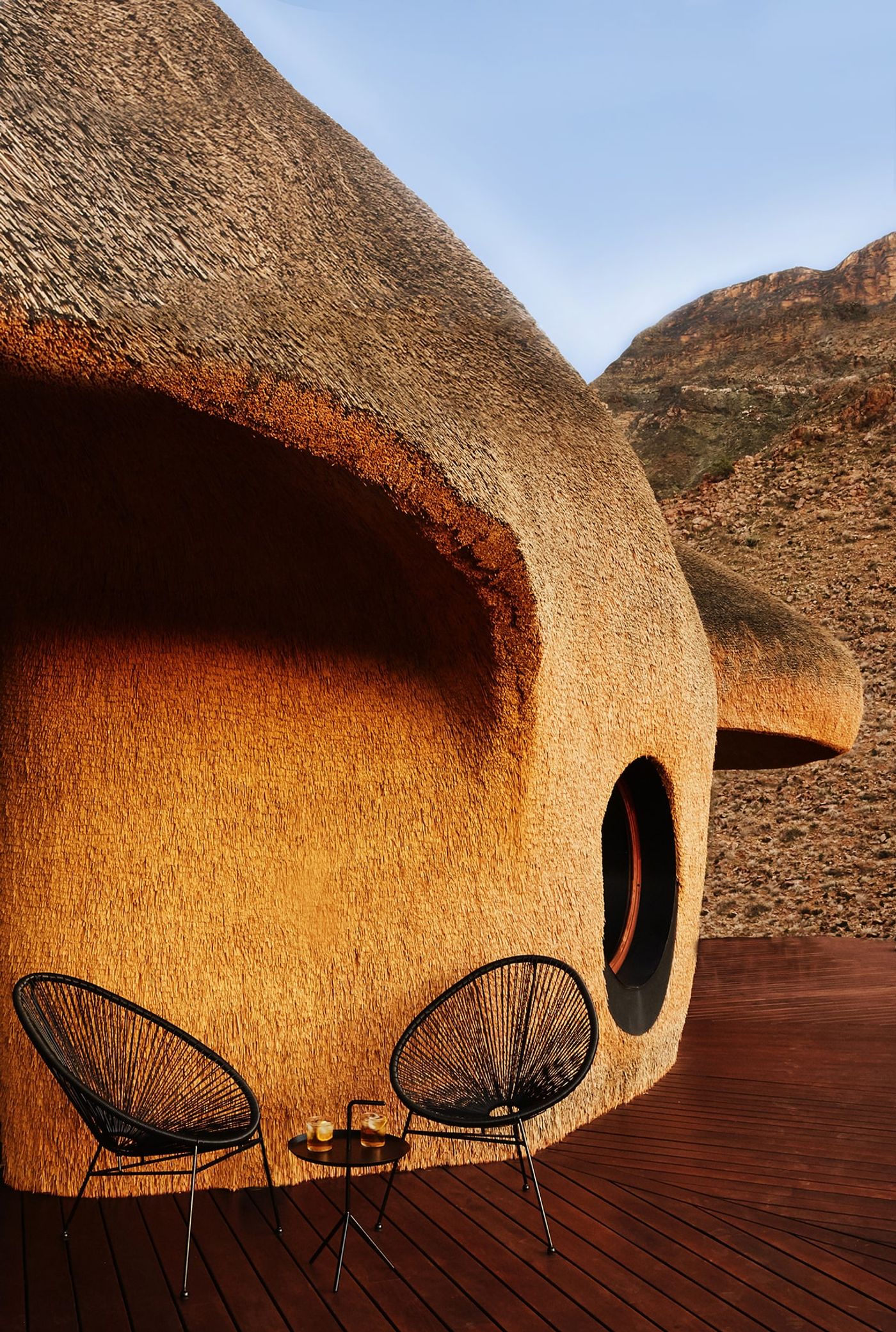

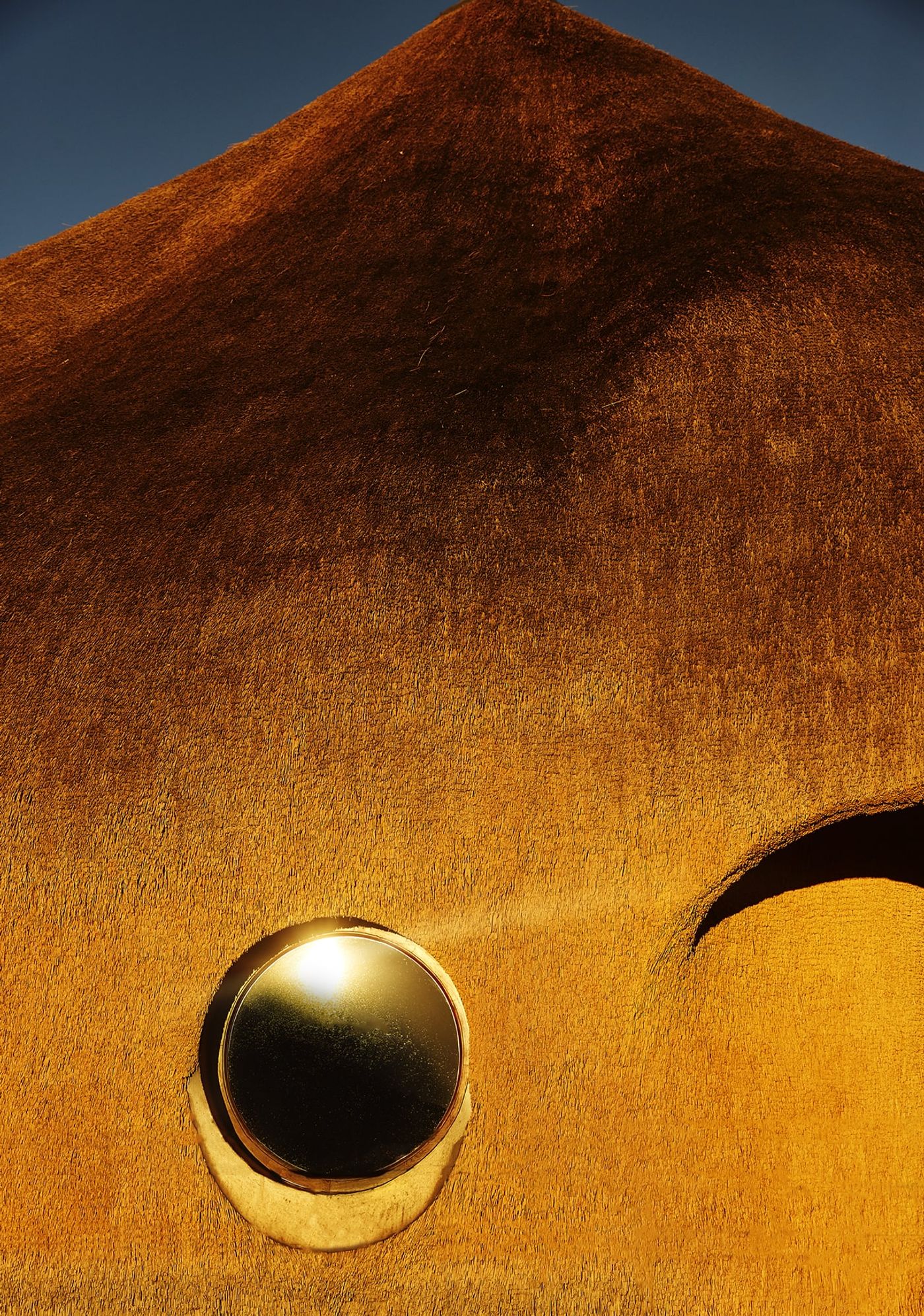

Developed in collaboration with Swen Bachran, the owner of the 24,000-hectare conservancy, the three-bedroom house is both startlingly primitive and futuristic. Fittingly named The Nest, the structure has been inspired by the extraordinary nests built by sociable weavers, a sparrow-like species endemic to southern Africa, which populate the property. Housing hundreds of birds with multiple entrances for each family, they are a marvel of engineering not least because unlike most nests they continue expanding rather than being abandoned when the chicks grow up.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

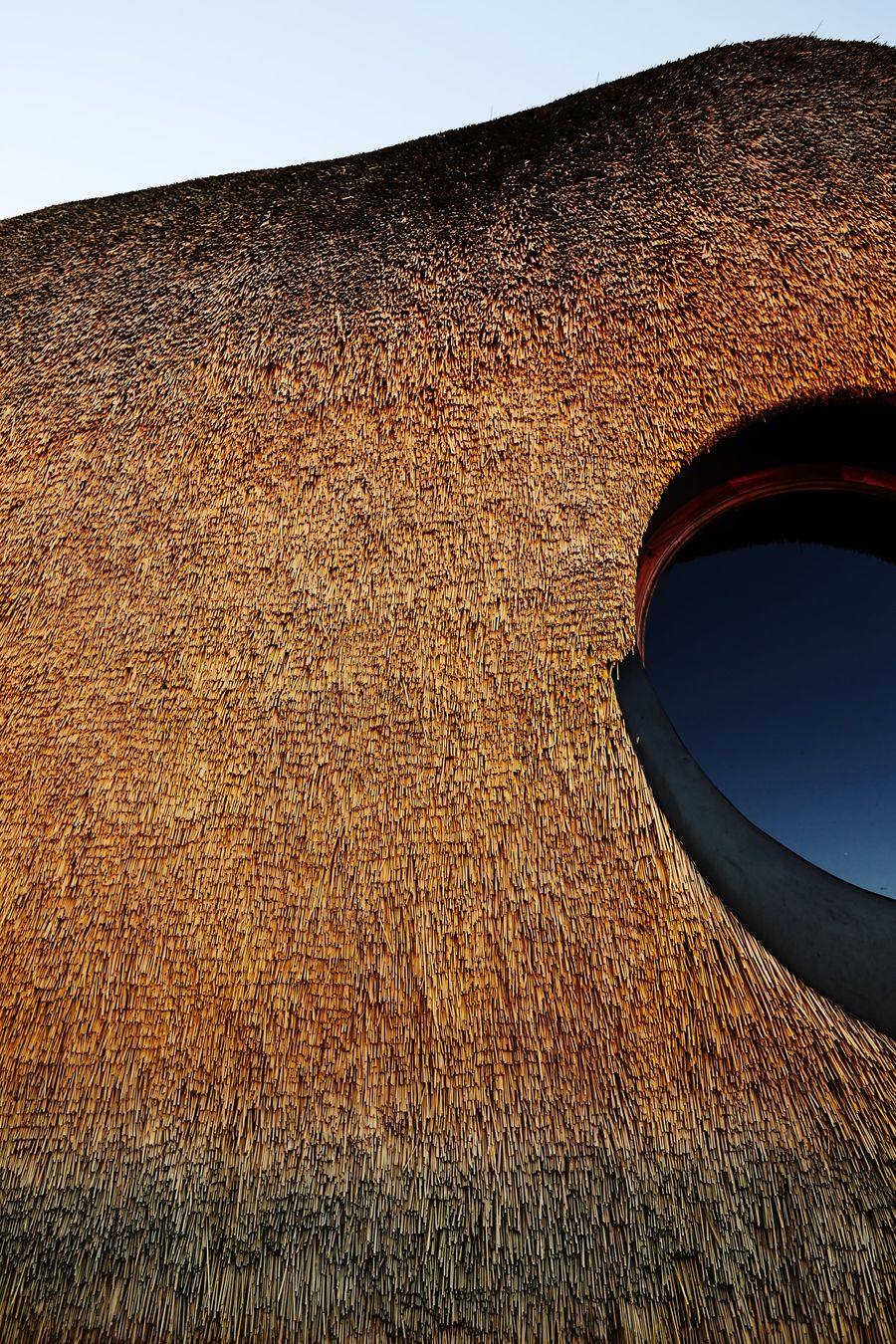

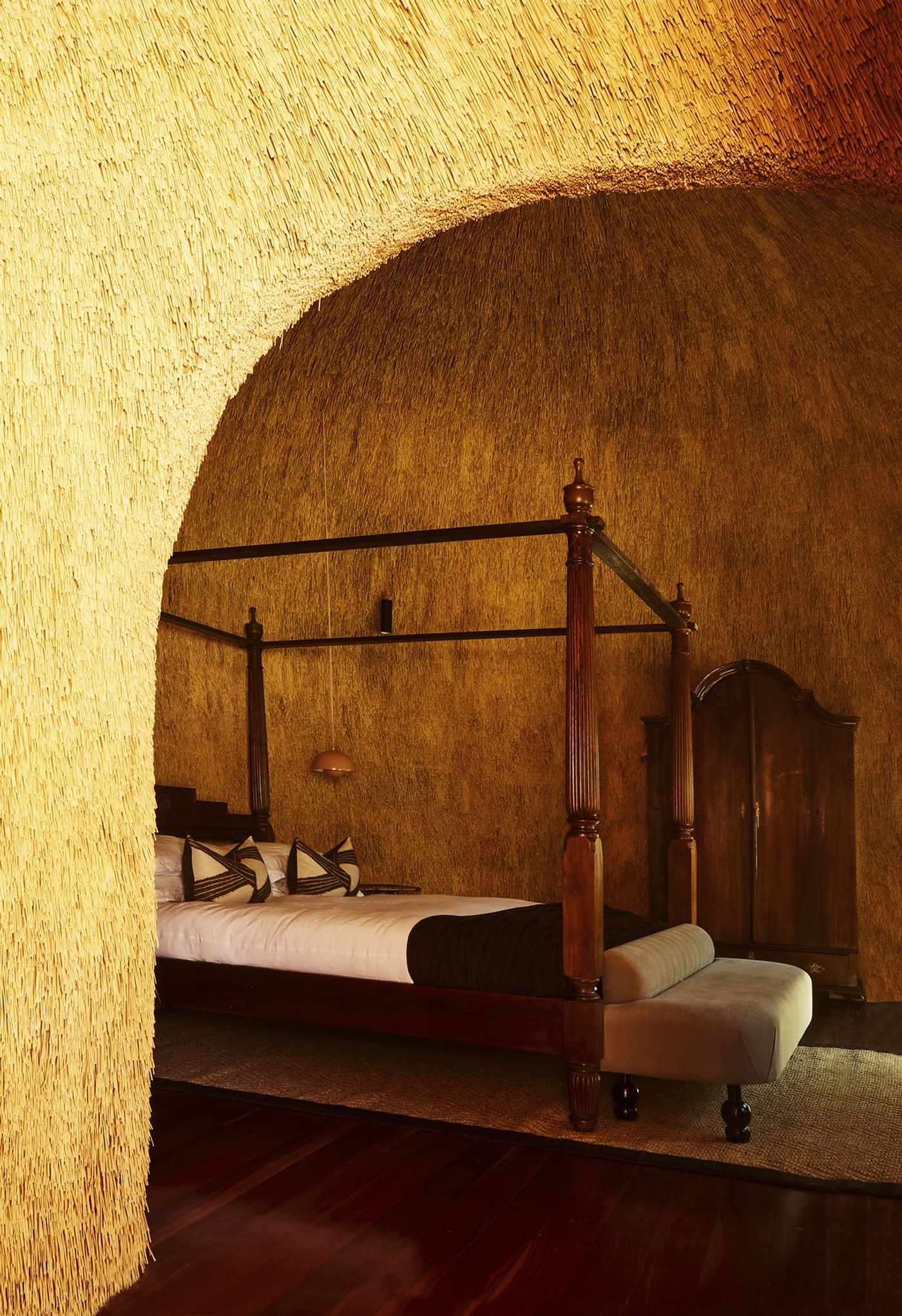

Using natural materials, locally sourced whenever possible, the house has been designed to seamlessly blend into its desert context, while the hand-crafted interior designed in collaboration with Yelda Bayraktar and Maybe Corpaci, features bespoke, in-built furniture rhat attest to Hefer’s holistic approach. Primitive as it may seem – made as it is with local stones, hand-made bricks and reeds sourced from the banks of the Zambezi River – the retreat doesn’t lack comforts or amenities, with its own swimming pool and helipad (the nearest town is 125km away) as well as a chef and local guide on hand.

Yatzer recently caught up with the designer to chat about his project, which won best new private house in the 2019 wallpaper* awards, his interest in vernacular architecture and his passion for animals.

(Answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

How did The Nest come about? Was designing a house something you always wanted to do?

A while back I got a brief for a game lodge in Zambia. The structures were on a river that flooded every year and every time they would rebuild them using the reeds that grew due to the flooding. The idea you could build something that only needed to last 8 months was interesting, as was the fact that every year there would be more materials to use, which I realized was like a bird building a nest. Exploring this concept, I proposed something different than the cubic structures they were building – if it didn't work, we could always build something different the next year – but they didn’t go for it. Over the next few years, I talked to various other safari operators and land owners, but with no luck. I strongly believe luck, and ultimately success, is based on timing.

And then I met Swen Bachran. He was in the process of buying a farm in Namibia and asked my wife and me to accompany him. On the road to the farm I started noticing the increasing number of large nests built by sociable weavers on the telephone poles that lined the road, and the even larger nests on the ancient camel thorn trees that dot the landscape. We camped for a few days on the land he was considering purchasing where I got the chance to study them up close – there were 3 or 4 extraordinary structures which blew me away – and I realised the timing was right.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

This is your first architectural project. In which ways was your background as a furniture designer helpful and what were the challenges that this entailed?

I’ve always been interested in environments rather than furniture – most of my furniture pieces are environments. Most of my objects are small rooms that you disappear into - I like to entertain the imagination. For me the bigger the better, as it means you have more opportunity to capture a person’s imagination.

In design, communication is important when you are working with others, the more you communicate what you want and the more detail you provide, the better the results will be. This project was a big leap for most of the people involved, so I needed to provide a lot of information to ensure we all understood what we were making. I therefore sketched everything from every angle in as much detail as possible. It was a very organic process that allowed for changes to happen if necessary – if something proved to be impossible, we would work out what was possible. Everything, including the plans was hand-drawn so there was some leeway when it came to the construction.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

"In design, when you are working with others communication is important, the more you communicate what you want, and the more detail you provide, the better the results will be". -Porky Hefer

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

How did the project’s focus on sustainability and conservationism affect the house’s design? Were the restrictions that this approach imposed an impetus for creativity and innovation?

One of the basic principles of vernacular architecture, which is what really interests me, is the use of local materials, local techniques and local artisans which is why vernacular buildings are better suited for their environment and blend in more easily. They also boost the local economy and strengthen the local community.

For this project, it helped that the site was so far from Windhoek, the capital city of Namibia, as it was almost impossible to get materials sent from there, so going local was the obvious solution. The local materials are moreover perfectly suited to the harsh desert environment; besides anything foreign wouldn’t be able to cope with the elements or would get eaten up far quicker.

Also, the handmade bricks that we used saved us from transporting heavy loads on roads that were only fit for a 4x4 vehicles, while the use of stones from the site meant the walls disappear into the landscape.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Nests have long been a source of inspiration for you. What is their significance for you as a designer?

Birds build their nests in terms of form, not materials. They build the smallest form possible for their needs and use materials that are readily available within a certain radius at the time they are needed, which ensures that they blend into the environment rather than stand out. We need to learn from them.

I love the sounds birds make, their personalities and quirks. Birds amaze me, they make me smile, make me laugh. I recently had the privilege of witnessing the mating dance of a young male blue crane (our National bird) that was trying to impress a female. The wind was incredibly strong, so he soon started jumping up into the wind with his wings extended which suspended him in the air, almost as if he was in slow motion. The dance that followed was truly one of the most beautiful moments of my life.

Did the interior aesthetic naturally stem from the choice of building materials and construction method or was it part of the initial design concept?

Birds don’t use much furniture in their nests. In fact, the nest is the furniture. So the idea was to build the furniture into the structure as much as possible, creating one seamless structure with various functions, a good example of which is the sunken lounge in the centre of the main living space. All but one of the beds are built in, with the double bunk for the kids being the most fantastic. I wanted to create a space that you could move through easily so I didn't want the clutter that obstructs most homes these days.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

"I like to work with what people recognise and can relate to. I like to include rather than exclude, to simplify things rather than complicate". -Porky Hefer

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Animal iconography is an important inspiration in your practice. Where does this interest come from?

I was extremely fortunate and blessed to spend a lot of my childhood in nature. We would spend most weekends on a game farm near Johannesburg and frequently went on trips to game reserves like Kruger Park and the incredible reserves in KwaZulu Natal – it was my father’s way of keeping me and my three siblings entertained.

Nature mesmerised me and got my imagination running wild, I felt at home there. I was always surrounded by animals, both wild and domestic. Some of my best friends were animals: dogs, horses, ostriches, sheep, mice, lovebirds, fish, rhinoceros, beetles, spiders and snakes, they all lived in my pocket or bed – in fact, while working on The Nest I shared my bed with a cheetah and a Karakul cub. Animals don't judge you like humans do. They are honest (although cats can be a bit tricky) and do what they feel.

I read at a young age that early science fiction creators looked through microscopes for inspiration rather than up towards space. If you look closely, you'll see that the insects in your garden look a lot like the crowd in a bar in a Star Wars movie. Watch the movie Microcosmos and it will blow your mind.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Your work is underpinned by a whimsical sensibility. How important is this aspect of your work and why?

I think it is very important to connect with people on a positive note. I like to work with what people recognise and can relate to. I like to include rather than exclude, to simplify things rather than complicate. The way I see the world is very different to most. I notice little things and brief moments which make me smile. I think a lot about things that most would find trivial or inconsequential, it’s in the little things that I get my pleasure.

What would you love to design next?

A structure for me and my wife to live and work in. We have just moved to the South of France and we are looking for the perfect environment to do it. It’s the land of Andre Bloc, Pierre Szekely, Jaques Couelle, Valentine Schlegel, Claude Costy, Henri Mouette, Pascal Hausermann, Daniel Grataloup and Antti Lovag, so I’m definitely in the right place.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

Photo by Katinka Bester.

"I find nature fascinating. There is so much drama and beauty happening every second". -Porky Hefer

Portrait of Porky Hefer.Featuring Buttpuss, from the series Plastocene – Marine Mutants From a Disposable World. Photo Antonia Steyn, courtesy Southern Guild.