BEST OF BEIRUT DESIGN WEEK 2018

Words by Eric David

Location

Beirut, Lebanon

Beirut, Lebanon

Location

Beirut Design Week (BDW), now in its seventh edition, may not be as established as Milan’s or as glamorous as Dubai’s, but has something unique going in its favor, namely the city of Beirut. One of the oldest cities in the world, it has been a commercial and cultural hub on the crossroads between the East and the West for the past five millennia. Badly wounded during the fifteen-year civil war that rocked the country from 1975 to 1990, Beirut has since risen from its ashes with a relentless zest for renewal that combines the breakneck fervor of an adolescent with the experience of a septuagenarian. This paradoxical sensibility makes for a fertile ground for an endeavor such as BDW to grow and flourish, fueled by the city’s rich heritage and the creative zeal of its people.

“Design & the City”, the theme of this year’s fair that took place from the 22nd to the 29th of June, 2018, turned its attention to its host city by exploring how design can transform the urban environment and the experience of its citizens. Drawing inspiration from and harnessing the power of local grass-root movements, BDW 2018 called upon designers to reclaim the city and rekindle citizen participation. Yatzer was present in Beirut and has collected the best that the fair had to offer.

Little Bricks, Big Message by Dispatch Beirut whose work was part of the public interventions at Jeanne d'Arc Street.

Mike lounge chair by Local Industries. Photo by Mothana Hussein. © 2018 Local Industries

Independent Beirut exhibition in partnership with Adorno and Fabraca Studios. "De Vil Legacy" table & "Lizard King" rocking chair by Coco Exotico. Photo by Taim Karesly © 2018 Adorno ApS

From the beginning, we really tried to balance the luxury product part with the social-environmental part, so that the designers that are just focused on luxury see the relevance of design for social impact.—Doreen Toutikian, Co-founder & Director of Beirut Design Week

Beit Beirut hosted exhibitions and roundtable discussions. Photo by Taim Karesly.

Beit Beirut hosted exhibitions and roundtable discussions. Photo by Taim Karesly.

Although BDW2018 was a decentralized fair with exhibitions, workshops, open studios and happenings all over the city, its heart beats at Beit Beirut, “the House of Beirut”, a building in Achrafieh that evocatively encapsulates both the city’s glorious past and the civil war that devastated it. Originally known as the Yellow House or the Barakat building, on account of its ochre colour and patron family respectively, the four-storey apartment building was built in 1924 by prominent Lebanese architect Youssef Aftimus in the Ottoman revivalist style. During the tumultuous years of the civil war it found itself in the green zone and was turned into a sniper’s den. Badly damaged, it was left abandoned after the war ended and would have been torn down if it wasn’t for the passion and dedication of architect, activist and community organizer Mona El Hallak who has spent the last 24 years trying to restore it into a museum celebrating the memory of Beirut, a herculean task of immense bureaucratic and financial hurdles.

Although not yet opened to the public, Beit Beirut, which has at last been renovated, crucially without totally erasing its wartime scars, hosted several concurrent exhibitions during BDW2018 but just as importantly it functioned as a symbol for the transformative role of design in commemorating the city’s past whilst paving the way for its future.

Beit Beirut hosted exhibitions and roundtable discussions. Photo by Taim Karesly.

The Photo Mario Archive Project exhibition at Beit Beirut. Photo by Eric David.

Independent Beirut exhibition in partnership with Adorno and Fabraca Studios. Works by (clockwise from top left) Cocoexotico, Christian Zahr, Wyssem Nochi, Toofic Matta and Rita Kettaneh. © 2018 Adorno ApS

Two exhibitions at Beit Beirut a caught our eye, Independent Beirut, an eclectic collection of furniture, lighting and ceramics by emerging Lebanese designers, and The Photo Mario Archive Project, an evocative display of a photographic archive that was discovered by Mona El Hallak behind rusting roller shutters—all that was left of “Photo Mario”, a once thriving studio located on the ground floor of the building. Displayed amidst walls pitted with bullet holes and marked by graffiti, the unknown faces on the warped, stained and torn negatives look back at you melancholically, inviting you to intuitively flesh out their stories.

Whereas the The Photo Mario Archive Project looks to the past, the Independent Beirut exhibition looks steadfastly to the future shining a spotlight on emerging regional designers whose work captures the character, scope and creative spirit of modern Lebanon. Conceived from BDW’s inception as a platform for independent creatives to reach a wider audience, this year’s show is a collaboration between Danish online digital gallery and sales platform Adorno and local manufacturing company Fabraca Studios. What’s more, a selection of this year’s works curated by Ghassan Salameh, BDW Managing & Creative Director, constitute the “Beirut Collection”, Adorno’s first collection of design devoted to Beirut, the 12th global city to be represented, on sale now through its website.

“One Drop” table (detail) by Abdo el Moudawar, part of Adorno's Beirut Collection. © 2018 Adorno ApS

Independent Beirut exhibition in partnership with Adorno and Fabraca Studios. “One Drop" table by Abdo el Moudawar and "Rock’nJug" by Toofic Matta. Photo by Taim Karesly © 2018 Adorno ApS

Independent Beirut exhibition in partnership with Adorno and Fabraca Studios. Low marble table by Thomas Trad, Neural Network by NOAH Architects and UNEARTHLY pottery series by Zeina Aboul Hosn and Marianne Sargi. Photo by Taim Karesly © 2018 Adorno ApS

Low marble table by Thomas Trad, part of Adorno's Beirut Collection. © 2018 Adorno ApS

Low marble table by Thomas Trad, part of Adorno's Beirut Collection. © 2018 Adorno ApS

Some of the exhibits that caught our eye were Thomas Trad’s impeccably crafted low tables in marble and wood, whose organic shape and low height was inspired by the traditional Japanese low tables or Chabudai; Paola Sakr’s “Impermanence”, a series of hefty vases made of abandoned pieces and material scraps such as concrete bollards and brass rods; and Abdo el Moudawar’s “One Drop”, a handmade brass table whose shape wondrously captures, as the name suggests, the moment when a drop of water impacts onto a liquid surface. Also worth mentioning are Zeina Aboul Hosn and Marianne Sargi’s “UNEARTHLY” collection of hand-crafted and hand-glazed ceramic objects that look like mysterious fungi that have sprung up in an imaginary forest.

UNEARTHLY series of ceramic objects by Zeina Aboul Hosn & Marianne Sargi, part of Adorno's Beirut Collection. © 2018 Adorno ApS

UNEARTHLY series of ceramic objects (detail) by Zeina Aboul Hosn & Marianne Sargi, part of Adorno's Beirut Collection. © 2018 Adorno ApS

Concruence chair by Guillame Crédoz, part of ABOUT TIME exhibition of Beirut Makers at Beirut's Jewellery Souks. Photo by Mego Toumayan.

View of Jeanne d'Arc Street after the refurbishment. Photo by Taim Karesly.

Another pivotal location of BWD2018 was Jeanne d’Arc Street where, in collaboration with the American University of Beirut (AUB) Neighborhood Initiative, a series of urban interventions transformed it into a model street for the city. Connecting the AUB with Hamra Street, the neighborhood’s commercial artery, Jeanne d’Arc Street is used by both local residents and university students who until recently had to deal with narrow, obstacle-filled and litter-strewn pavements, symptoms of the city’s systemic indifference for public spaces. With the contribution of the municipality, the street underwent a major renovation that saw the removal of 23 parking spots to make way for pedestrian friendly and disabled-accessible pavements.

The interventions that were unveiled during BDW further forge the street’s credentials as a test ground for urban renewal. From the installation of Adrian Muller’s sleek receptacles for cigarette waste, and the introduction of a tagging system documenting the area’s trees and bird species, to “Red Reading Hood”, a red sitting booth that doubles as a public library that was designed by District D, and the use of LEGO blocks by Dispatch Beirut, an urban art initiative, to patch up traces of war and symbolically reclaim the street, all the projects exemplified BDW’s community-led ethos and the impact design can have in improving everyday life in the city.

Little Bricks, Big Message by Dispatch Beirut whose work was part of the public interventions at Jeanne d'Arc Street.

Nathalie Harb' Silent Room was part of the urban interventions at Jeanne d'Arc Street. Photo by Taim Karesly.

One of the most visionary projects on display was Nathalie Harb’s “Urban Hives”, a prototype design that aims to create green spaces on top of parking spots. Made out of scaffolding, a ubiquitous sighting in Beirut, the structure, painted a bright turquoise, is topped by a small garden underneath which cars can park in the shade. A few blocks down the road, in an empty lot where a beautiful early 20th century apartment building once stood—one more casualty of the city’s unconstrained growth that treats its architectural heritage as a nuisance—visitors had a chance to experience Harb’s “Silent Room”, an installation that was first presented in last year’s BDW. As its name suggests, the pink-coloured timber structure contains a public-private, introverted space where visitors are cleansed of the sounds and sights of the city.

By far the most unique intervention that we saw was “between a thought and another”, a rotating planter-cum-bench part of BePuplic, a project by 3rd and 4th year AUB Architecture Students. Located in front of a mini shopping mall, in a small plaza that used to be used for parking, the elongated planter can be rotated, much like a dial, to point to one of the seventy inscriptions etched on a metallic bezel on the ground, each one corresponding to a shop nearby. The installation not only highlights the interdependent relationship between public and private land and commemorates the close ties of local business to the neighborhood, but also provides a sui generis playground for neighborhood children.

BePublic's “between a thought and another”, a rotating planter-cum-bench that was part of the urban interventions at Jeanne d'Arc Street. Photo by Taim Karesly.

BePublic's “between a thought and another”, a rotating planter-cum-bench that was part of the urban interventions at Jeanne d'Arc Street. Photo by Taim Karesly.

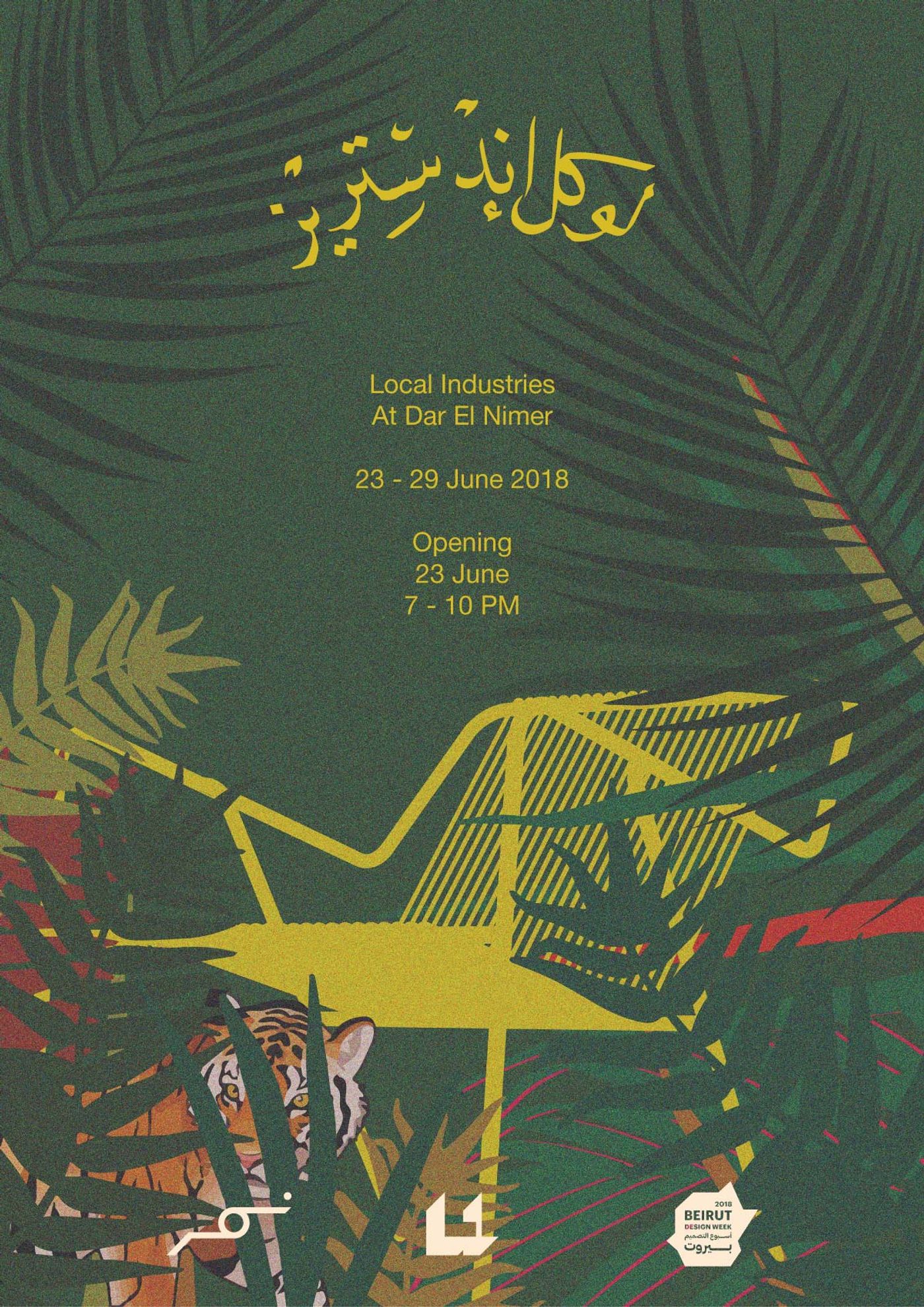

Dar El Nimer hosted the Local Industries exhibition and roudtable discussions. Photo by Taim Karesly.

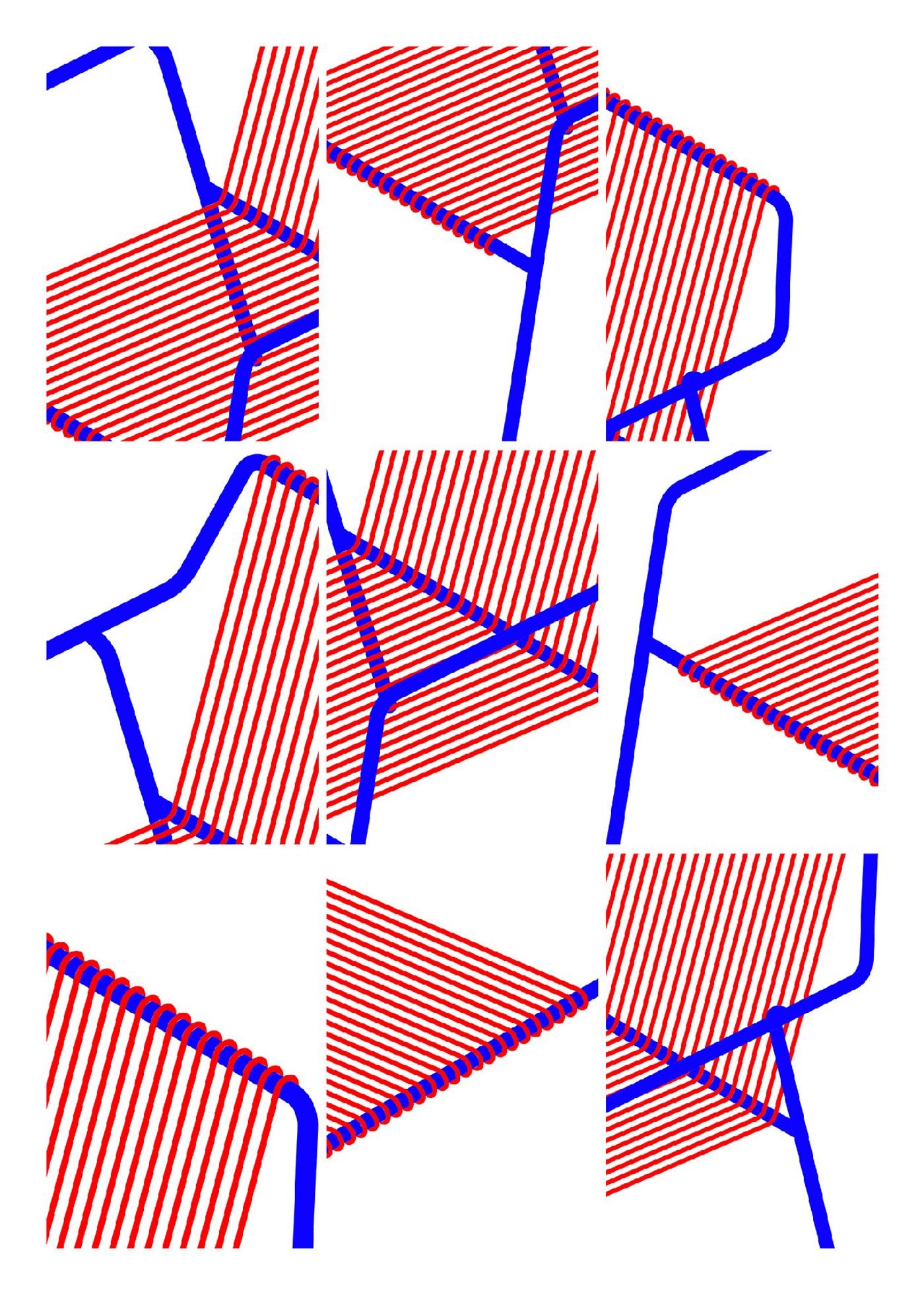

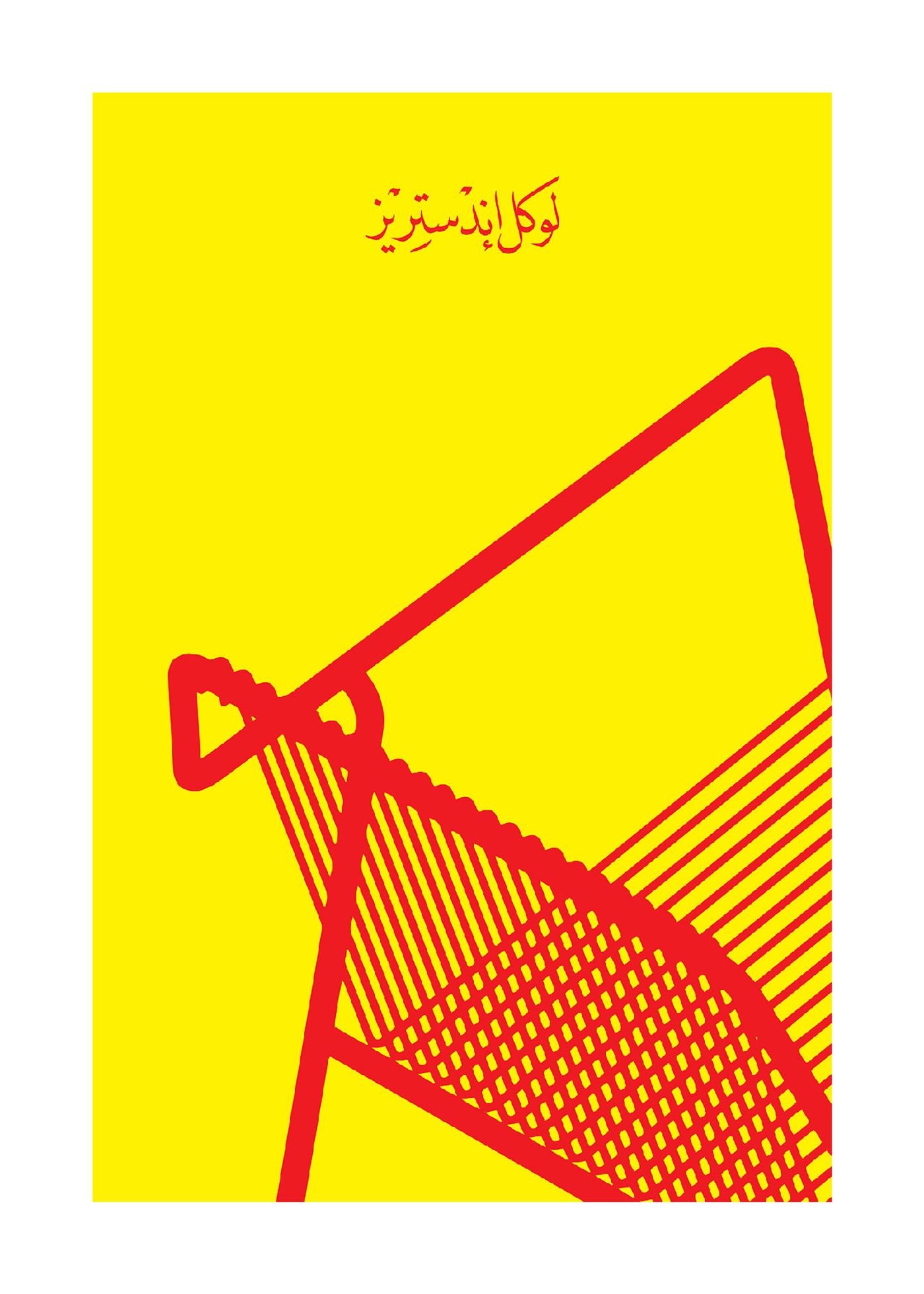

Not far from Jeanne d’Arc Street, is Dar El Nimer, a modernist 1930’s villa turned cultural venue, whose recently renovated exhibition space hosted Local Industries, a Bethlehem-based furniture-making venture by Palestinian architects Elias and Yousef Anastas. Founded in 2011 in parallel with their architecture projects, Local Industries combine modern design with Palestinian craftsmanship in an effort to promote local artisans in the face of sociopolitical constraints as well as explore the synergies between designing and manufacturing. The collection on display, which ranged from lounge and dining chairs to a rocking two-seater, impressed with their exuberant color palette of sleek blues, reds, greens and orange, their modernist design and their lightweight construction made from galvanized and powder coated steel tubes and rods. Quite graphical in sensibility, they were fittingly accompanied by a number of fun, iconographic posters that capture the spirit of the collection through a bold Pop Art aesthetic.

Jamil dining chairs by Local Industries. Photo by Elias Anastas.

Mike collection by Local Industries. Photo by Elias Anastas.

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz

Another designer that caught our eye was French-Lebanese Carla Baz, whose collection of marble tables, light fittings and shelving units was exhibited in Joy Mardini Design Gallery. Titled “Stratagems”, the collection is both an elegy to marble and a bold exploration of its potential. Working with a wide range of marble hues, Baz transforms her primal matter into smooth organic forms of minimal thickness that highlight the marble’s fragility and delicacy. Uncannily, the collection’s low tables feature a layer of colored resin that appears like a pool of liquid.With a trove of small design studios that were open to the public throughout the city highlighting the multidisciplinary dynamism of the Lebanese design scene, and with a plethora of workshops promoting creative collaborations, BDW 2018 offered visitors a kaleidoscopic taste of the creative fervor that simmers underneath Beirut’s urban momentum.

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz.

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz

Stratagems series by Carla Baz. Exhibited at Joy Mardini Design Gallery during Beirut Design Week 2018. © Joy Mardini Design Gallery and Carla Baz.