All Art is Political: Giuseppe Stampone’s Conceptual Craftsmanship

Words by Eric David

Location

All Art is Political: Giuseppe Stampone’s Conceptual Craftsmanship

Words by Eric David

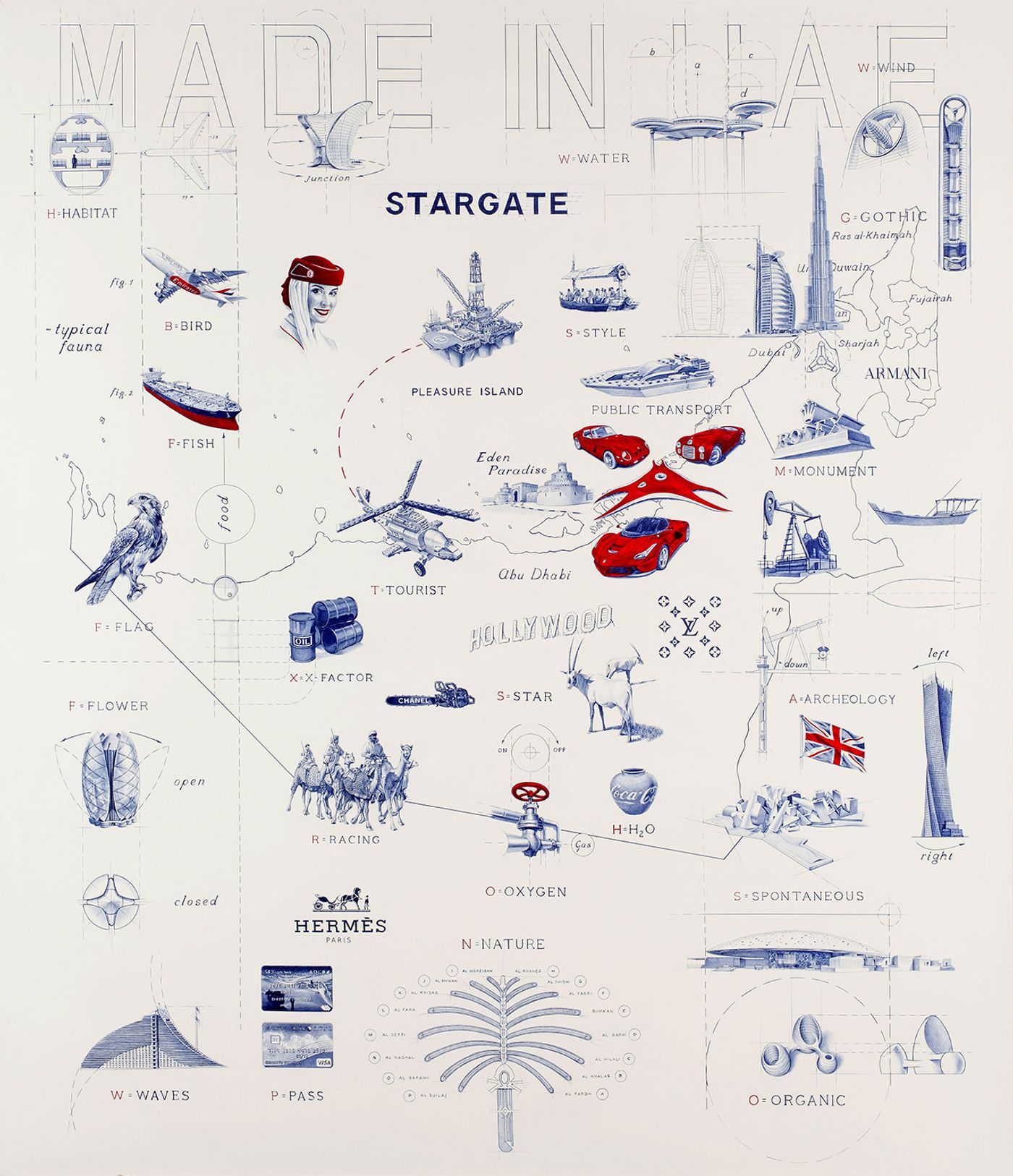

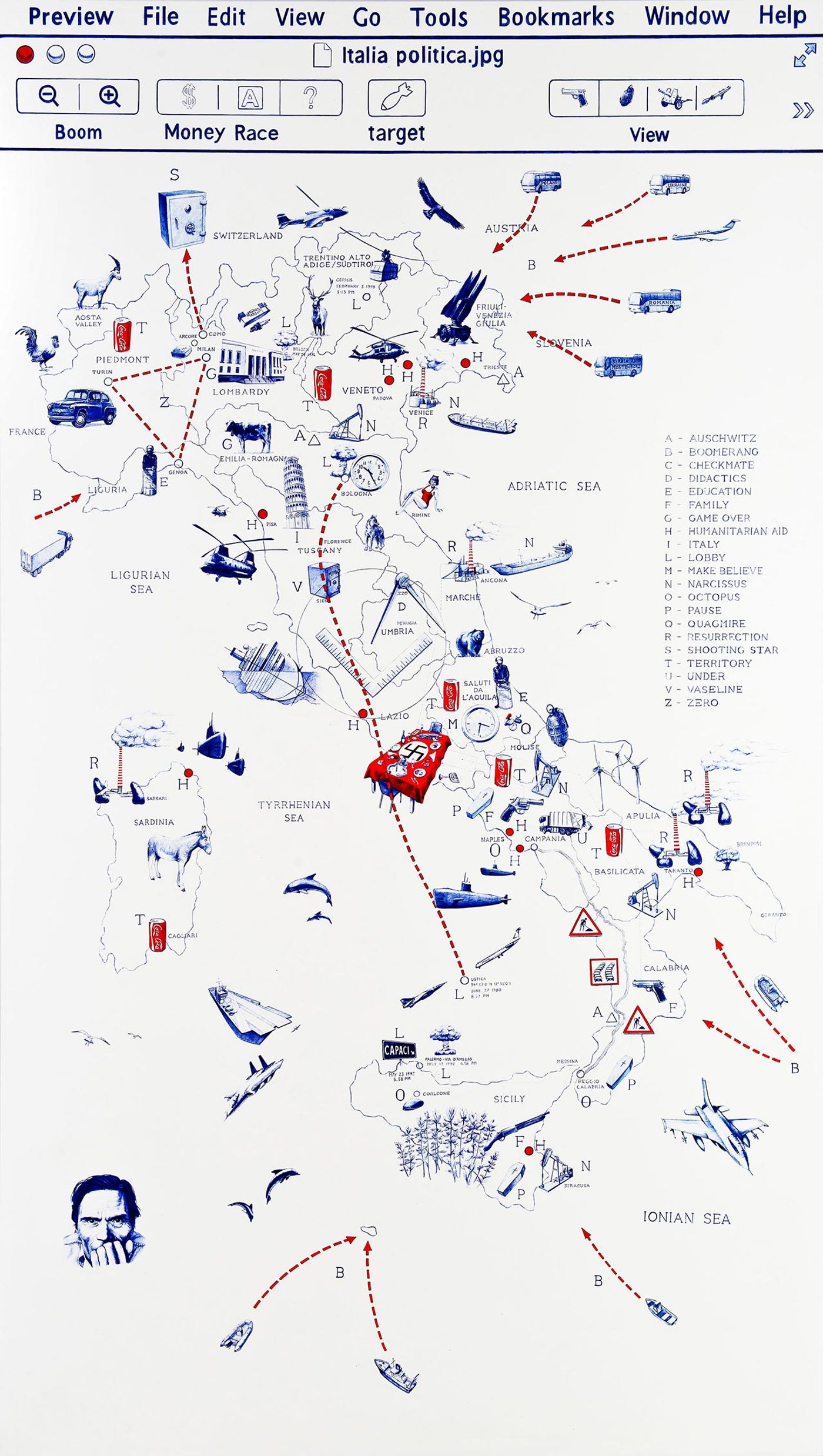

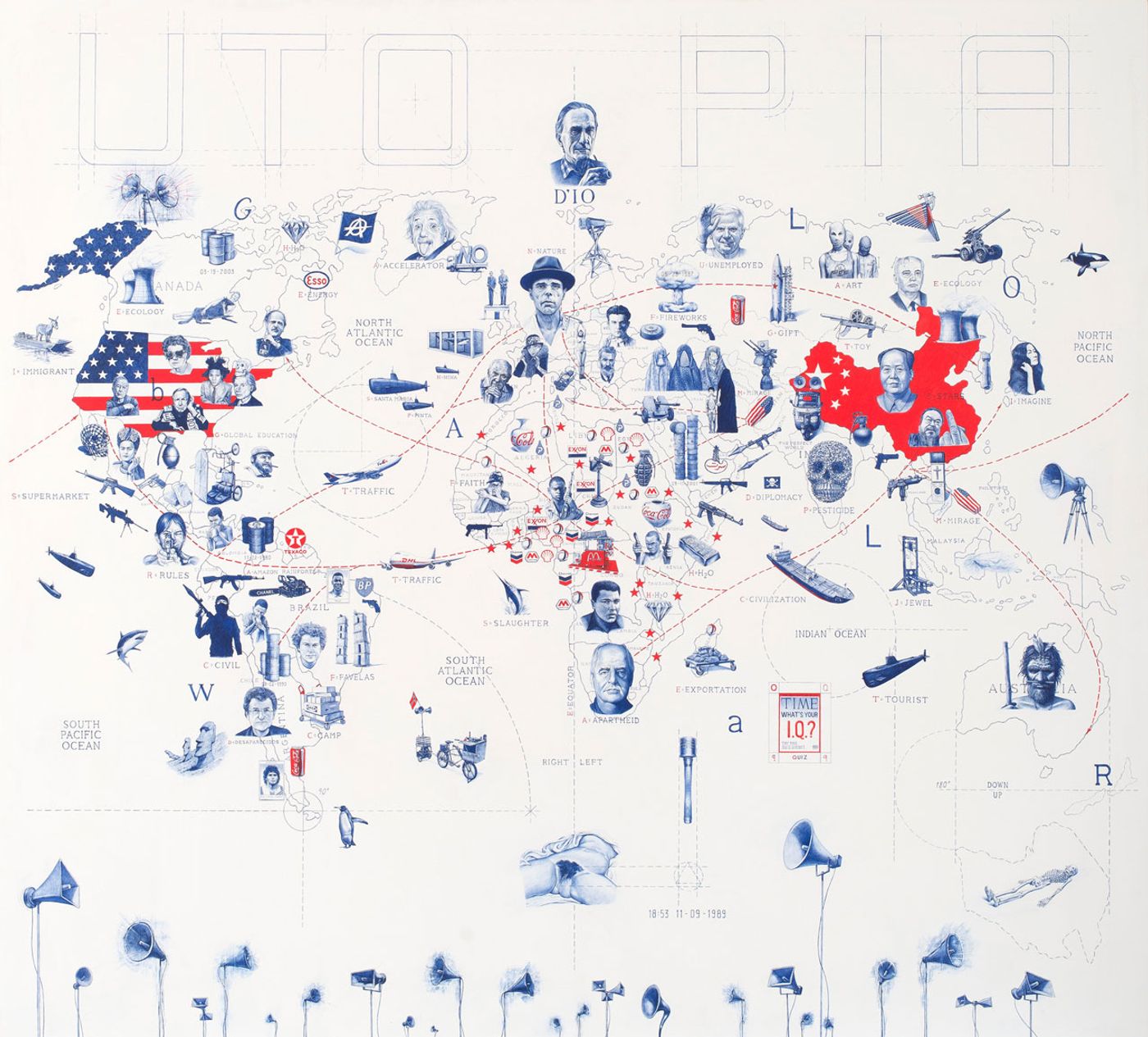

Italian conceptual artist Giuseppe Stampone admits he is “neither a draughtsman nor a painter”, preferring instead the epithet “intelligent photocopier”. And copy he does, prolifically, appropriating ephemeral images from the internet, iconic pictures from pop culture and works of classical art, and transferring them to paper using a ballpoint pen. It is a time-consuming and painstaking process that nevertheless elicits physical pleasure. By transcribing their content in excruciating detail, Stampone is challenging the meaning of the original images, but more than that, he is manifesting political action: by stretching out time, the artist is purposefully disobeying the speed of the digital age we live in. Drawing from his own experiences, Stampone’s work tackles an array of international social and political issues such as immigration and colonialism, placing ethical commitment before aesthetics and political activism before neutrality in order to take a stance. Stampone talked to Yatzer about his work, his obsession with Piero della Francesca, and the lessons we can draw from the Japanese tea ceremony.Giuseppe Stampone is represented by MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

(Answers have been edited for brevity.)

Giuseppe Stampone, Golden Residencies (Malta), 2016. 200x15x90 cm, bic pen on mattresses © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

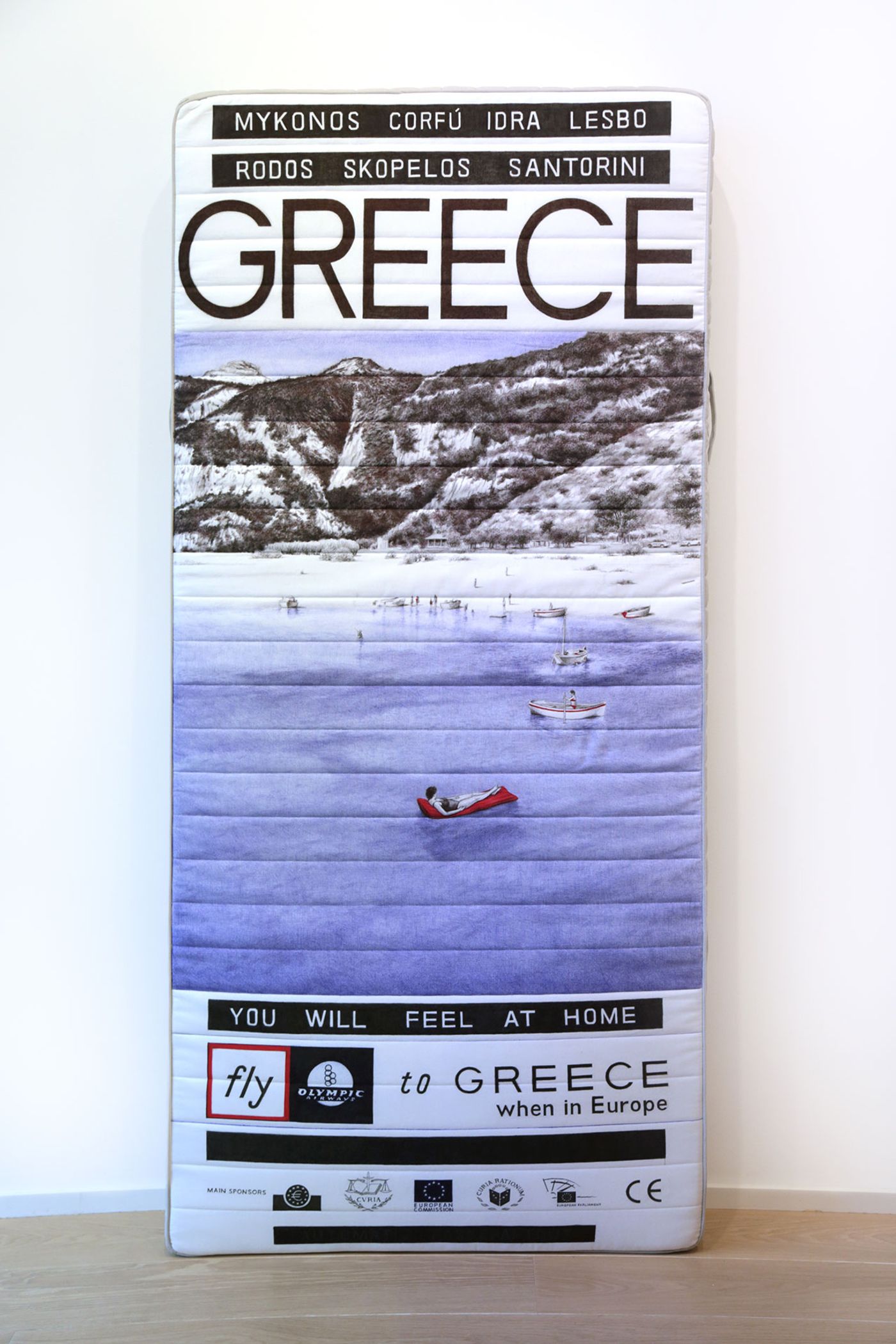

Giuseppe Stampone, Golden Residencies (Greece), 2016. 200x15x90 cm, bic pen on mattresses © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

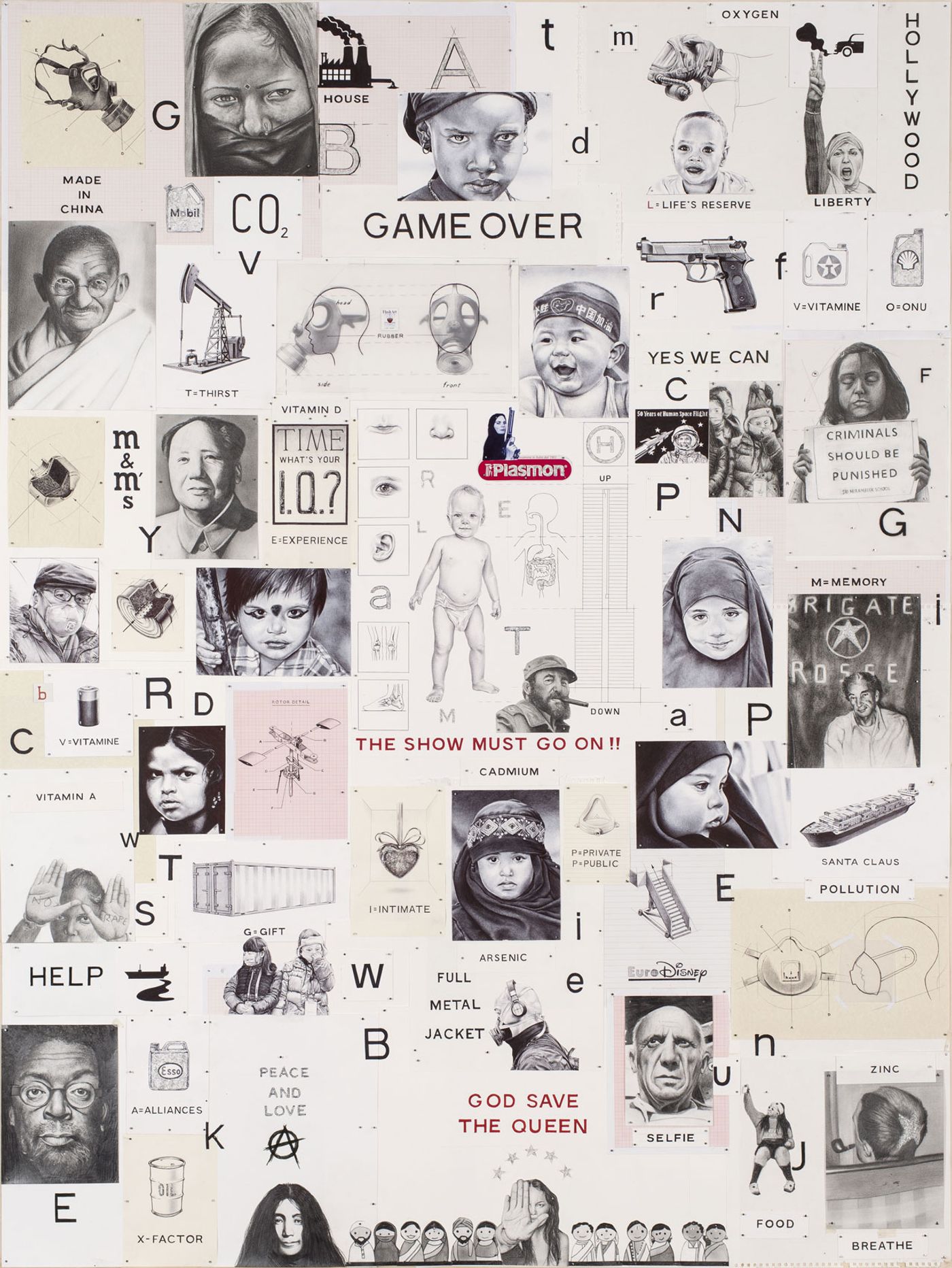

Giuseppe Stampone, The Show Must Go On, 2016 | Bic pen on paper,

176 x 150 x 22 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Atlantis, 2015. Bic pen on paper, 140×120 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Where do you trace your artistic sensibility? What prompted you to become an artist?

The will to breathe. To make an artwork, it is necessary to breathe, to live. Ever since I was born I have needed to represent the world around me, to experience it, analyse it, but most of all to take it all in, to breathe it. Breathing implies a living presence.

I believe art is a political issue. All art is political. Because when it isn’t political it is just decoration. A slash by Fontana is by no means less political than an artwork by Santiago Sierra, Alfredo Jaar or anybody else. Art is entirely political, because it takes a stance. Art is never neutral. It is never compliant; it is not interested in political compromise. Art always takes a definite stance, disobeying respectability and conformism.

Most of your drawings are created with a ballpoint pen. How did this come about?

I have always had an obsession with Piero della Francesca and the Renaissance. The Renaissance is recognized as the springboard for everything that came after, from artisanal art to fine and liberal arts, from craftsmanship to intellectual endeavours. It isn’t a coincidence that the Renaissance saw the birth of oil painting, at the same time Florence saw the development of Neo Platonic philosophy. It is then that capitalism and Euro-centrism began.

Flanders (on the other hand), the other cradle of oil painting, saw the development of a nominalist philosophy which believed it was necessary to place an emphasis on the dust under the table as well as the human who stood next to it. So how do you represent all this in a political way? Precisely by recognizing the same relevance in both of them. How do you do this? Through the sharpness of the painting: a human being is represented in the same quality as a dog, an apple, or a piece of bread on a table, with the same sharpness. It brings everything into HD focus without placing man at the centre.

Which brings us back to the question: why use a Bic biro? Because a Bic biro, like oil paint, contains a certain amount of oil inside it, and allows me to create stratifications of space time.

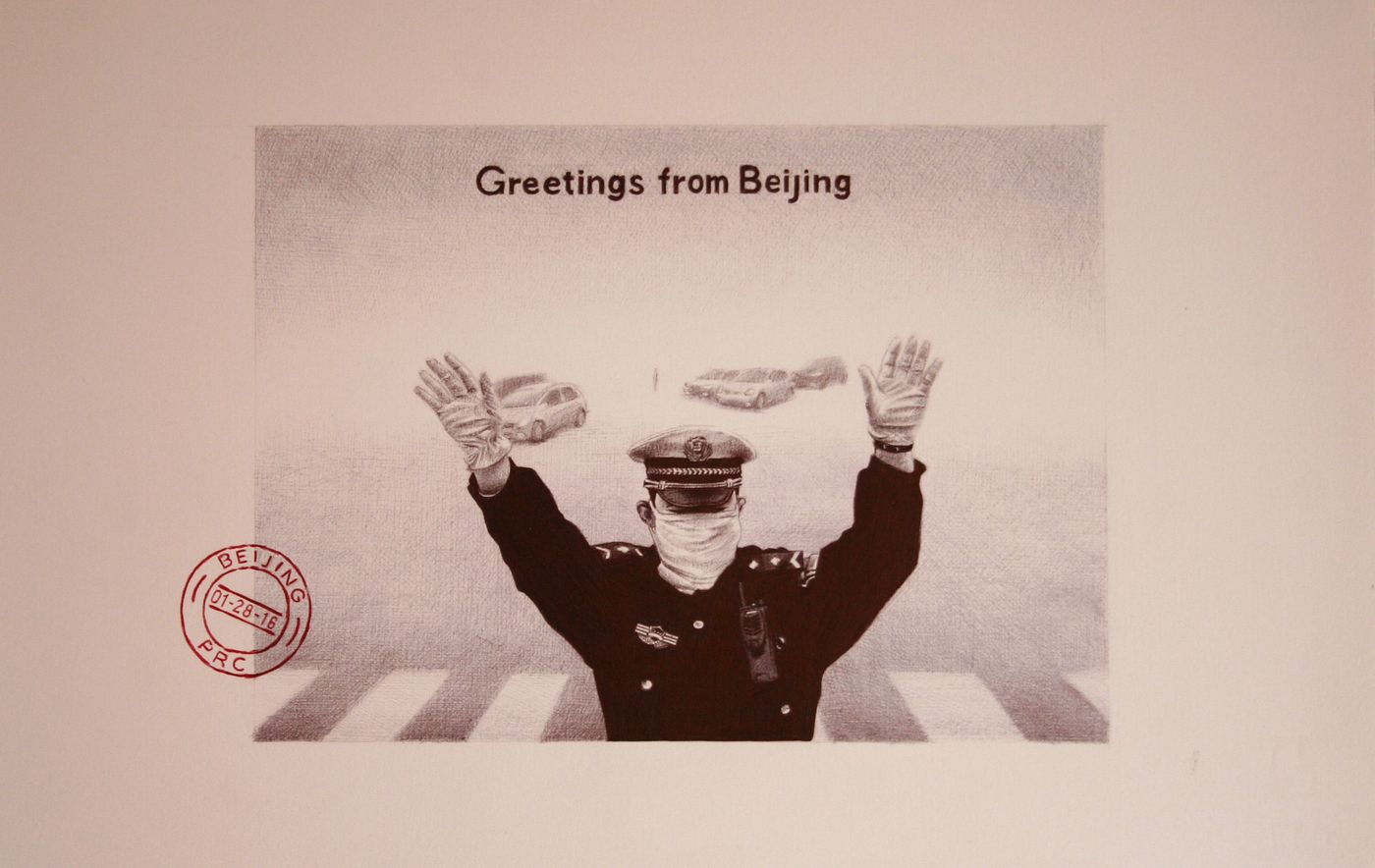

Giuseppe Stampone, Greetings from Beijing © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

You have cited that the reasons behind drawing with a pen is the aesthetic gratification that comes from the painstaking drawing process and the back-to-school connotations, as well as the “immortalization” of the ephemeral images, the “fluid fragments” that flood the internet. How important is the conceptual aspect of your art? Does the concept always dictate the method?

It is not exactly an aesthetic gratification; it is more a physical pleasure, because as I draw I manage to slow the flow of my time. Faced with the Internet and globalization I react by taking back my intimacy, repossessing my most intimate moments, and in doing so, I also achieve mental gratification.

Who nowadays can afford to draw, to enjoy oneself, to stretch time out again? The example I normally offer in response is that of the tea ceremony: this ritual takes an everyday aesthetic, like drinking tea, and turns it into an artwork. A master of tea will repeat the same ritual for thirty years. And it is precisely that repetition that will bring perfection.

Giuseppe Stampone, Made in Italy, 2012. Bic pen on prepared wooden board, 220×120 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Regarding your question about whether it is the concept that determines the method every time, the answer is yes. My actions are only conceptual: I challenge meaning which has become historical with a contemporary approach. I am obsessed by the image, by the iconography of the image, by what it represents, by the daily bombardment of images. I select images from the Internet, television and newspapers, wanting to make them immortal, crystallise them, defend them. Because nowadays we pay attention to forms, but never to the content that those images possess.

Giuseppe Stampone, Il Cielo è sempre più blu, 2013. Bic pen on prepared wooden board 200×220 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

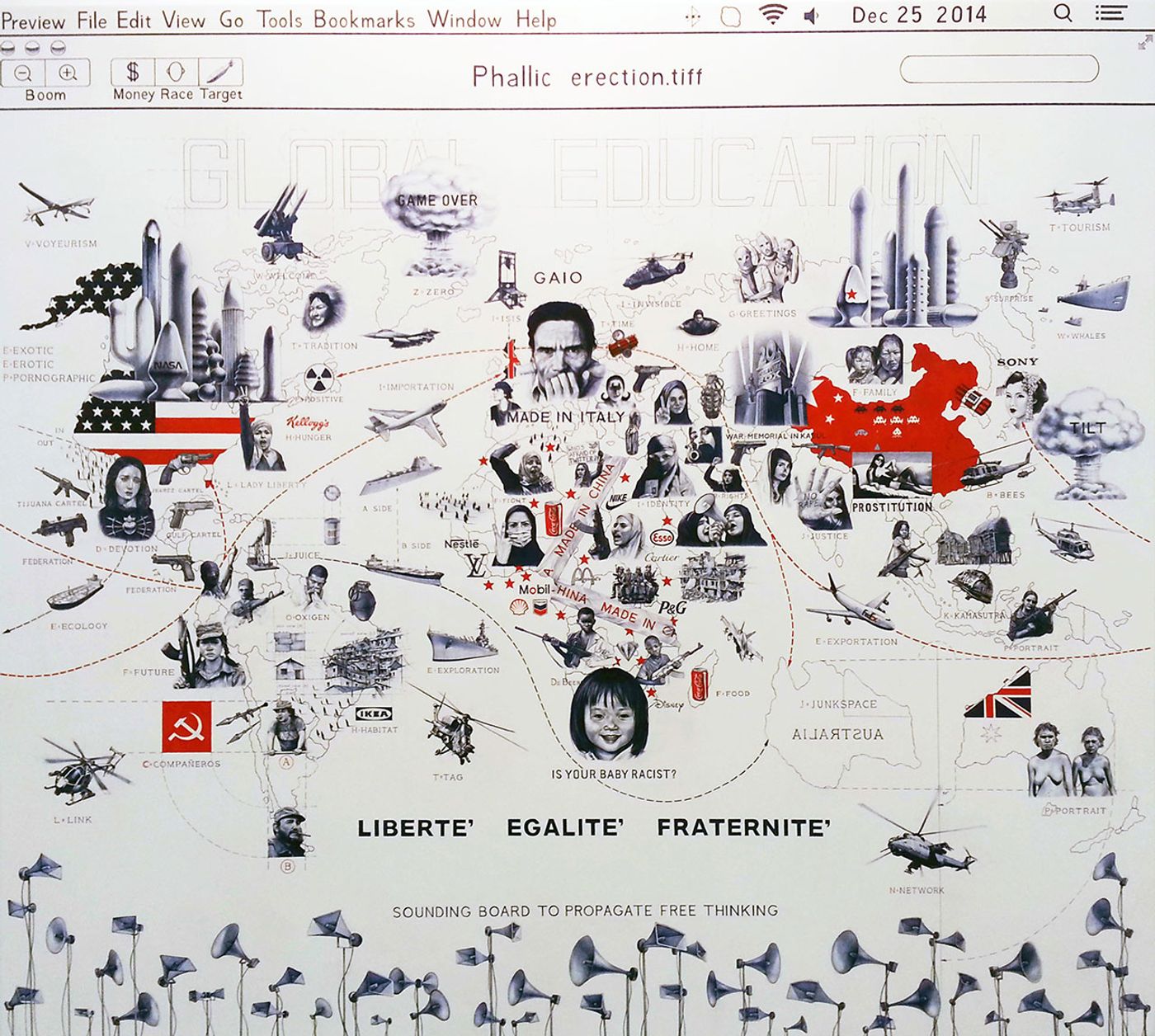

Giuseppe Stampone, Phallic Erection, 2014. Bic pen on prepared wooden board, 200×220 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, L'Origine du Monde, 2016. Drawing bic pen on wooden panel 30x40 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

You have described yourself as an “intelligent photocopier” as your artistic process relies on the act of reproduction, albeit the hand-made, analogue, one-off kind. This process is characterized by an inherent contradiction: the work you produce is by default derivative but at the same time unique. What is the significance of this contradiction?

Warhol called himself a machine, I call myself an intelligent photocopier, only making one copy.

In Fotocopiatrici Intelligenti (Intelligent Photocopiers) I draw liquid, iconic files from the Internet, and copy them just as they are. It takes two, three, even four or five months to make a file, so making it is no longer mannerist but conceptual: it implies the stretching out of time, and is my genuine disobedience to the speed of the Internet and globalization. What I want people to say in 100 years is while everybody else had a phallic erection, while everybody had to produce a hundred thousand photos, Stampone decided to remain in his studio, copy this file again and again, day after day like a monk, because it was a conceptual exercise to regain his own intimate time.

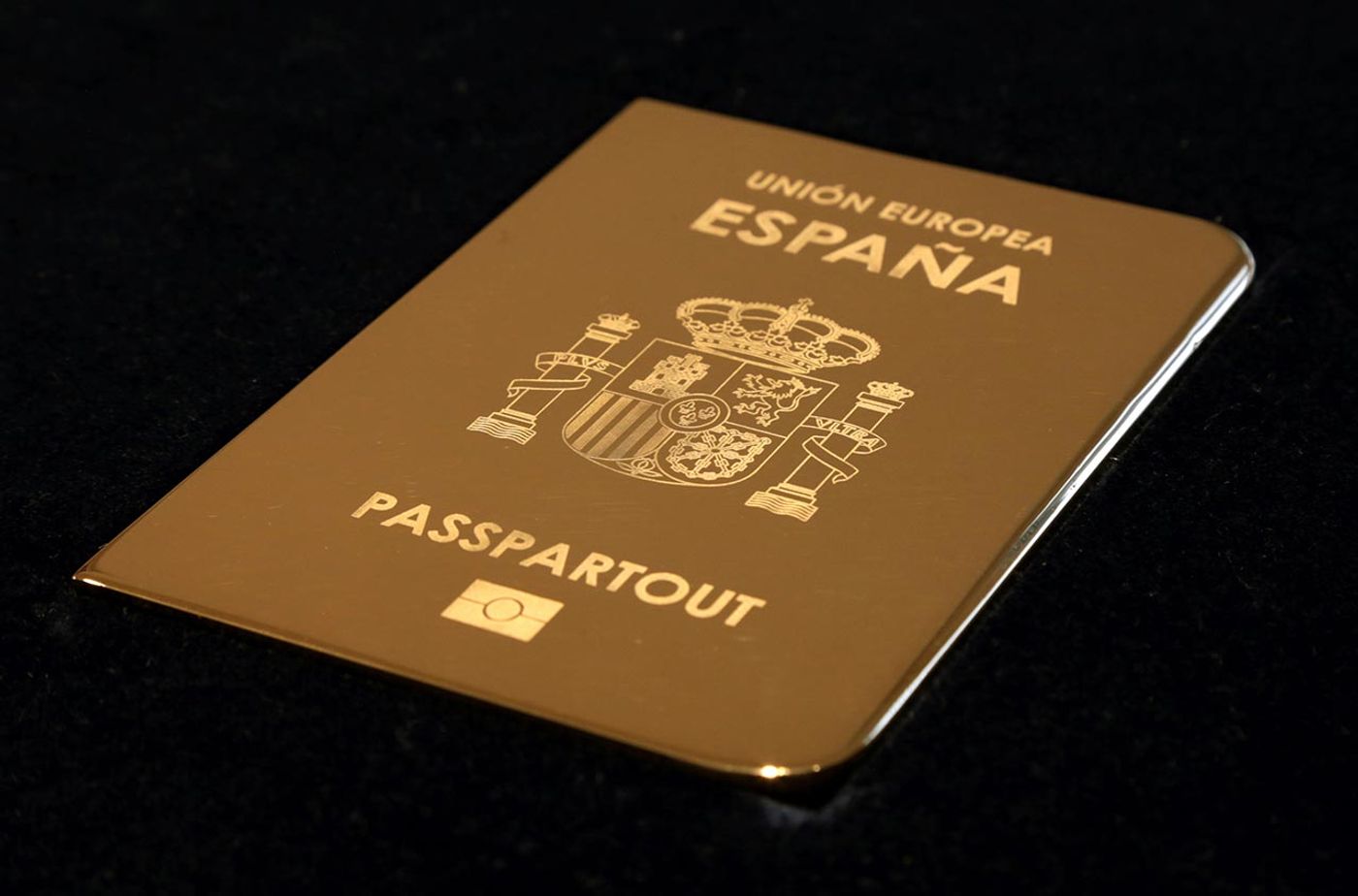

Giuseppe Stampone, Passepartouts, 2016; gold-plated cooper plate engraved 12,5x0,5x8,8 cm (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

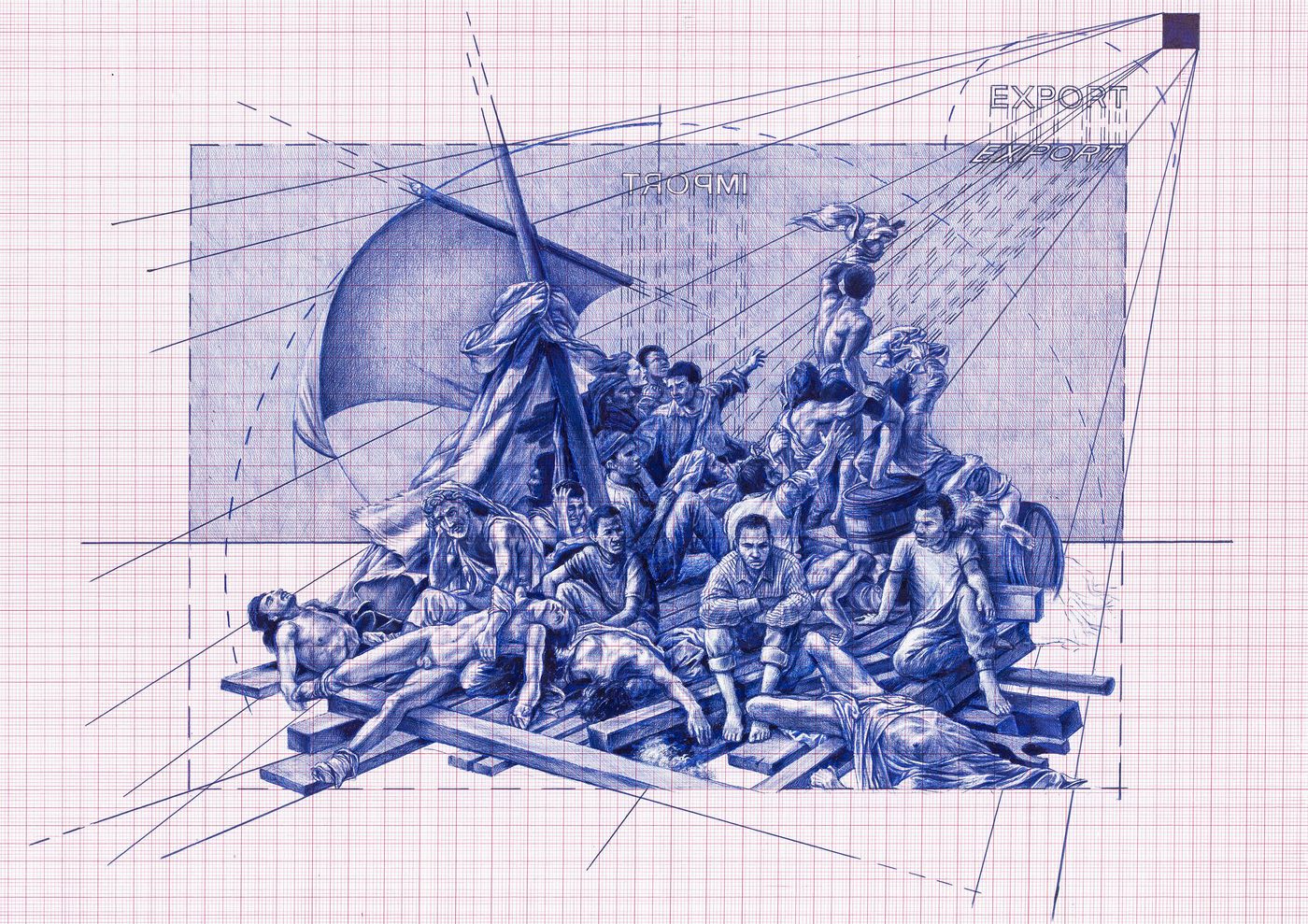

In your recent ballpoint pen drawings “Untitled - The Raft of the Medusa” and “Liberté, égalité, fraternité” you have reproduced Théodore Géricault’s famous 19th century painting in precise detail with the addition of some new castaways. Do these new human figures allude to the current immigration crisis and the immigrants drowning in the Mediterranean in particular? Are you also critically commenting on the elusive principles that the French Republic, and by extension modern western societies, were built on?

The raft of the Medusa, which will be exhibited at the Biennial of Migration, a project envisaged by Jan Fabre in Belgium, is a smaller version of that painting, measuring 30 x 40 centimetres.The Raft of the Medusa represents the failure of both the Napoleonic Empire and of the French Revolution, with France at the time being at the mercy of the waves. As you rightly point out, in this political painting I saw an image of today’s migrations. I see a Europe that is lost on this raft, losing an opportunity among these waves, and displaying its inability to save its present.

So I took some pictures of migrants landing in Lampedusa, I cropped out the people I was interested in and put them on the Raft of the Medusa in place of some of the historical figures.

How did I do that? Thanks to perspective. Like Piero della Francesca in the Flagellation of Christ, where he put together the death of his contemporary Oddantonio and the flagellation of Christ, I put together The Raft of the Medusa, an event that did not take place in my space time, with one that did.

In “Nel blu dipinto di blu”, a series of drawings where you have reproduced the covers of famous records, you have paired each cover with a different word/concept. What is the significance of these pairings and where did the series come from conceptually?

These are political images (like the Led Zeppelin album cover with the German zeppelin, the protagonist of the terrible catastrophe which took place in 1936 in New Jersey) with the themes of punk, rock or post punk music that I believe were the last epistemological breaks after Duchamp’s urinal. They break the tempo, the time, the music, they break the system, perspective and the diction, everything that is sequential and didascalic and everything that is right. They stand for what is not right, for the anti-everything. Punk has no rules, it stands in contrast to the bourgeois rules that had held things up till that moment and had blocked humanity (think of the UK under Thatcher). All that culture trying to break free has now been put back in its cage.

Giuseppe Stampone, Hiroshima Mon Amour, 2017 | Bic pen on wood,

40 x 30 x 4 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

In your “Golden Residencies” series you have reproduced touristic images on mattresses using ballpoint pens and embroidery. Why did you choose a mattress for your canvas for this series and what is the concept behind it?

There was a law in Italy that stated that if you went bankrupt, if you lost everything, they could take everything away from you, except your mattress. Your mattress was the last piece of property you were entitled to keep according to Italian law. That mattress then represented home, intimacy.

Provocatively, with these touristic images we were offering five star suites to these new emigrants, to these new homeless individuals. It all plays on the oxymoron between the touristic image that the tourist with money requires, and the emigrant’s mattress. There is a clear contradiction between expensive luxury tourism and the mattress it is represented on, i.e. the last element of survival and sustainability for a family.

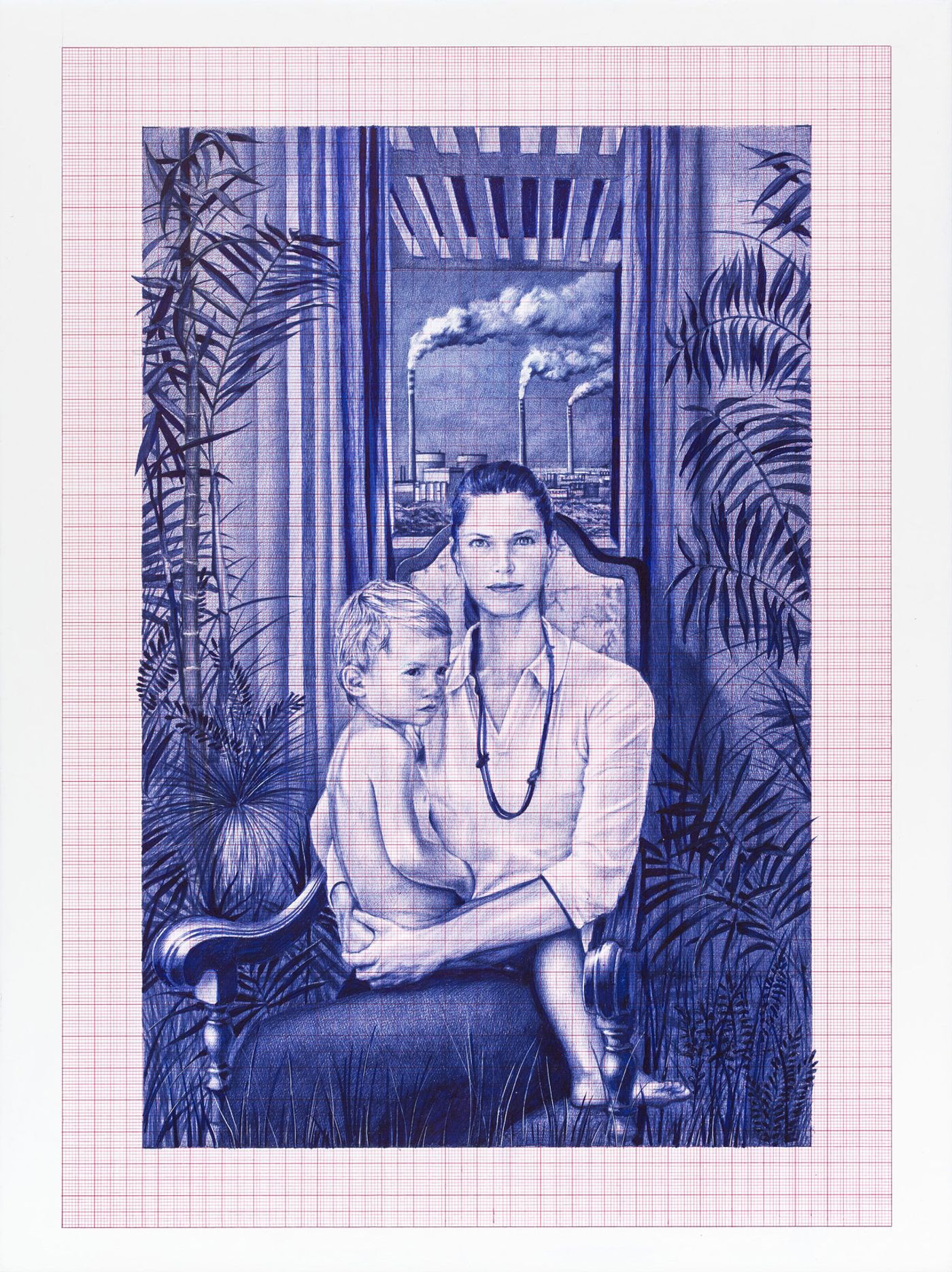

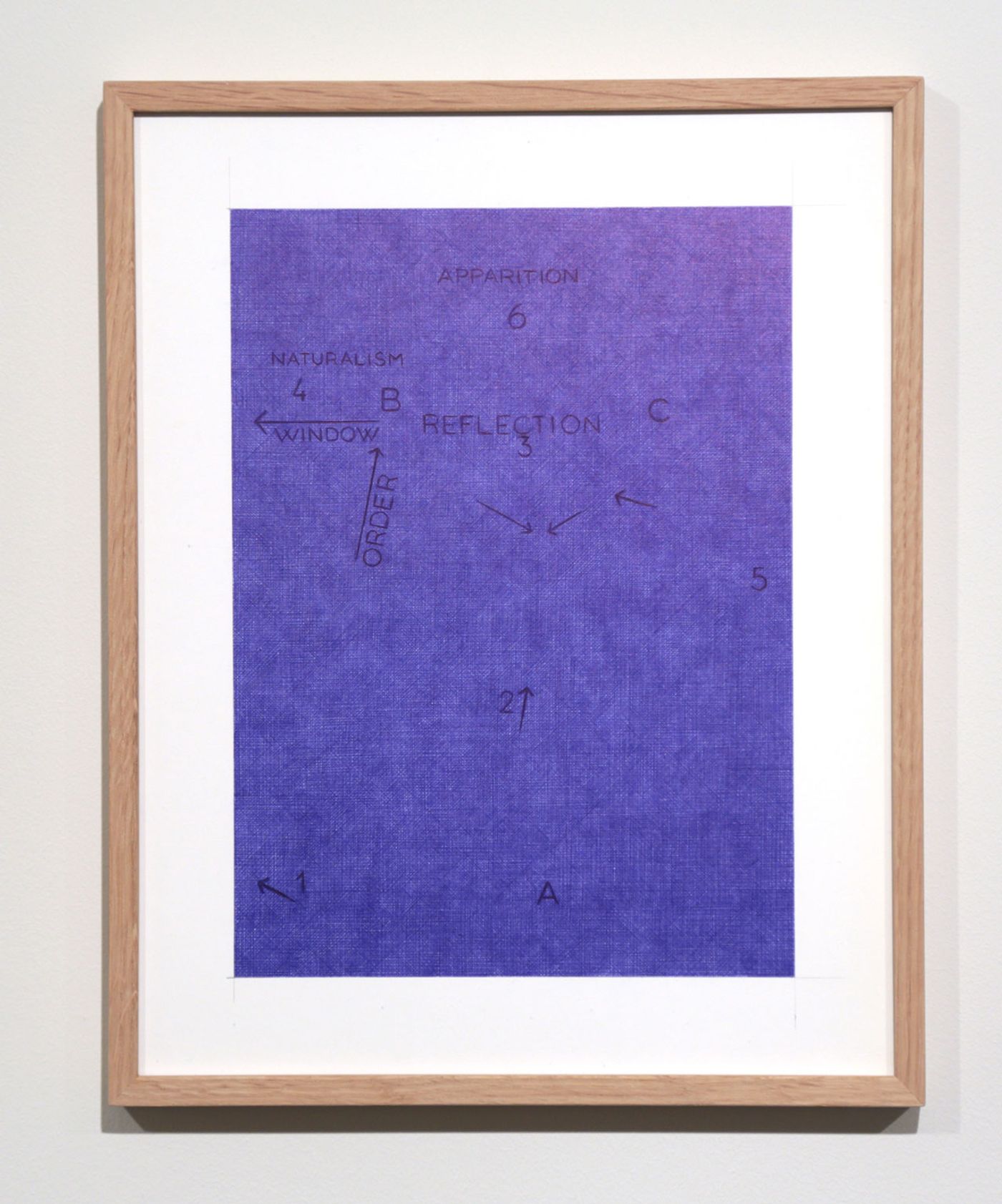

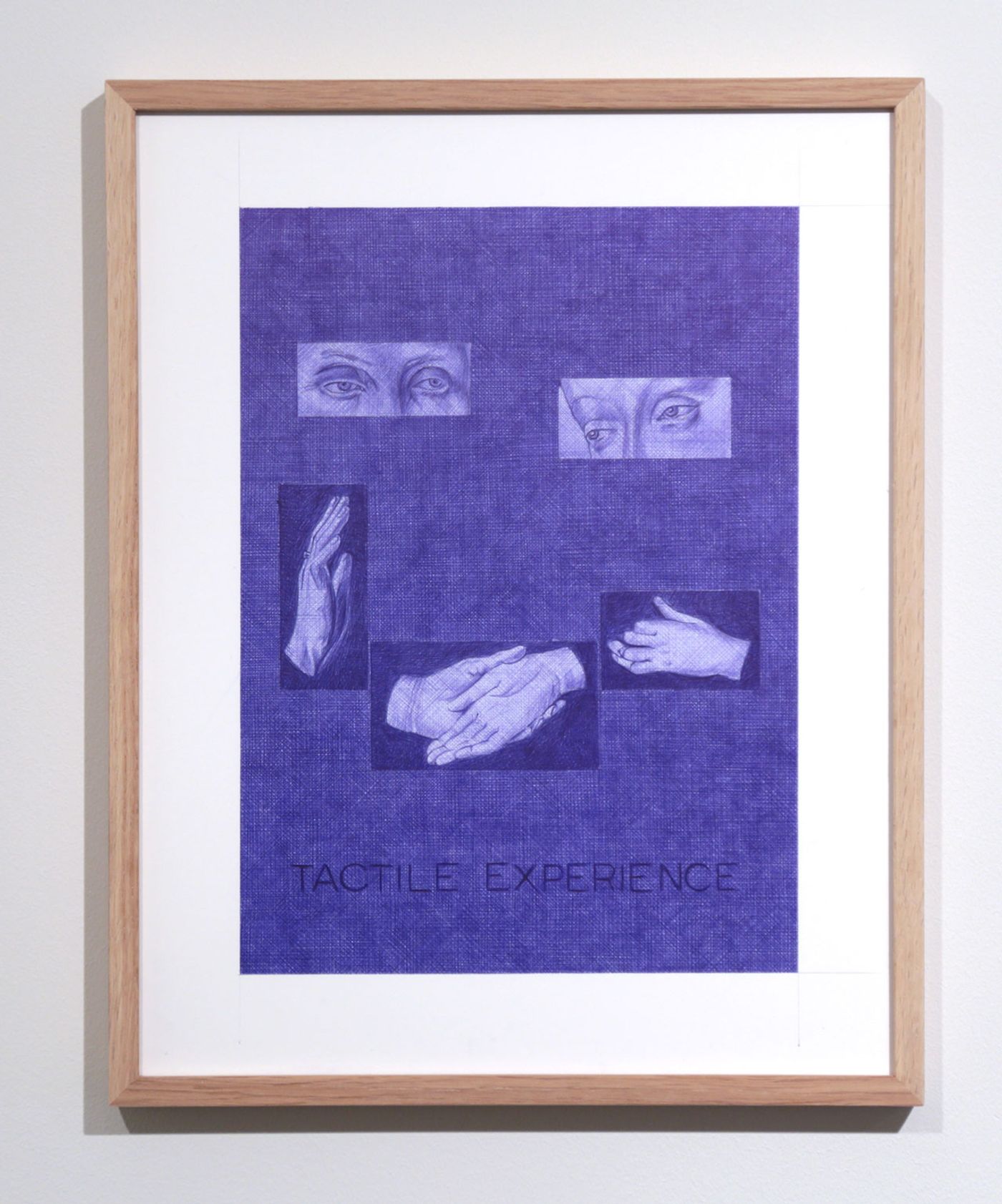

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste, 2016; 10 drawings bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

What are the advantages of the digital age for an activist-artist like yourself and what are disadvantages?

Many people consider the Internet to be a magic wand, a golden banner. The Internet is the global village, if you are not aware of your identity, if you are not yourself, you will be swept away.

The tsunami has arrived, the great wave, and we must learn to surf it. If we don’t have a personality we risk being swallowed up by the high seas of information. At the same time, the Internet is creating many phallic erections; many people see an opportunity for underhandedness because there is a lack of conscience. Before, it was possible to hide mediocrity, now mediocre people have nowhere to hide, they are immediately recognizable.

You have stated that the artist must return to ethical commitment before aesthetics. There is a strong belief in philosophical circles that moral perception and understanding of art are inherently bound up with its aesthetic appreciation. Do you share this view? Is there an optimum balance between the two or can they be autonomously pursued?

There is no single concept of aesthetics, or rather of beauty. There is no canon of beauty in the universe. There was never a standard of beauty. Beauty is a self-satisfied, self-righteous invention used to justify fashions or tastes of the moment.

Caution is necessary with regards to ethics, because what is now considered ethical could become a moral issue tomorrow. Ethics has a time, and a context. Ethics should never be conceived out of context, and most importantly it should not be read without consideration of the text, because the needs and the context change.

The truth of art is in its ethics. The truth of the artist is thus linked to time: with the passing of the years, ethics are changed by history. It is necessary for ethics, just as it is for art, to be set into the context and historic time frame that they belong to. Art has the opportunity to foresee and identify the inevitable evolution of ethical issues, with all that follows, even before they change.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité (La zattera della Medusa), 2017. Ball point pen on wooden panel, 40×30 cm © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

..........................................

Giuseppe Stampone participates at the international group exhibition “Het Vlot. Kunst is (niet) eenzaam / The Raft. Art is (not) Lonely” in the second edition of the international triennial exhibition in Ostend, Belgium.

Curated by Jan Fabre and Joanna De Vos the exhibition runs from October 22, 2017 to April 15, 2018

Address:

Galerie Teniers: Kerkstraat 11/38, 8400 Oostende, Belgium.

Opening hours:

Tuesday to Friday | 10 am - 6 pm

Saturday to Sunday | 2pm to 6pm

..........................................

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.

Giuseppe Stampone, Tentative Ecouchee d’une peinture utopiste (detail), 2016; bic pen on paper (particular) © Giuseppe Stampone, MLF | Marie-Laure Fleisch Gallery.