The Sociocultural Dialectics of Ali Cha'aban's Art

Words by Eric David

Location

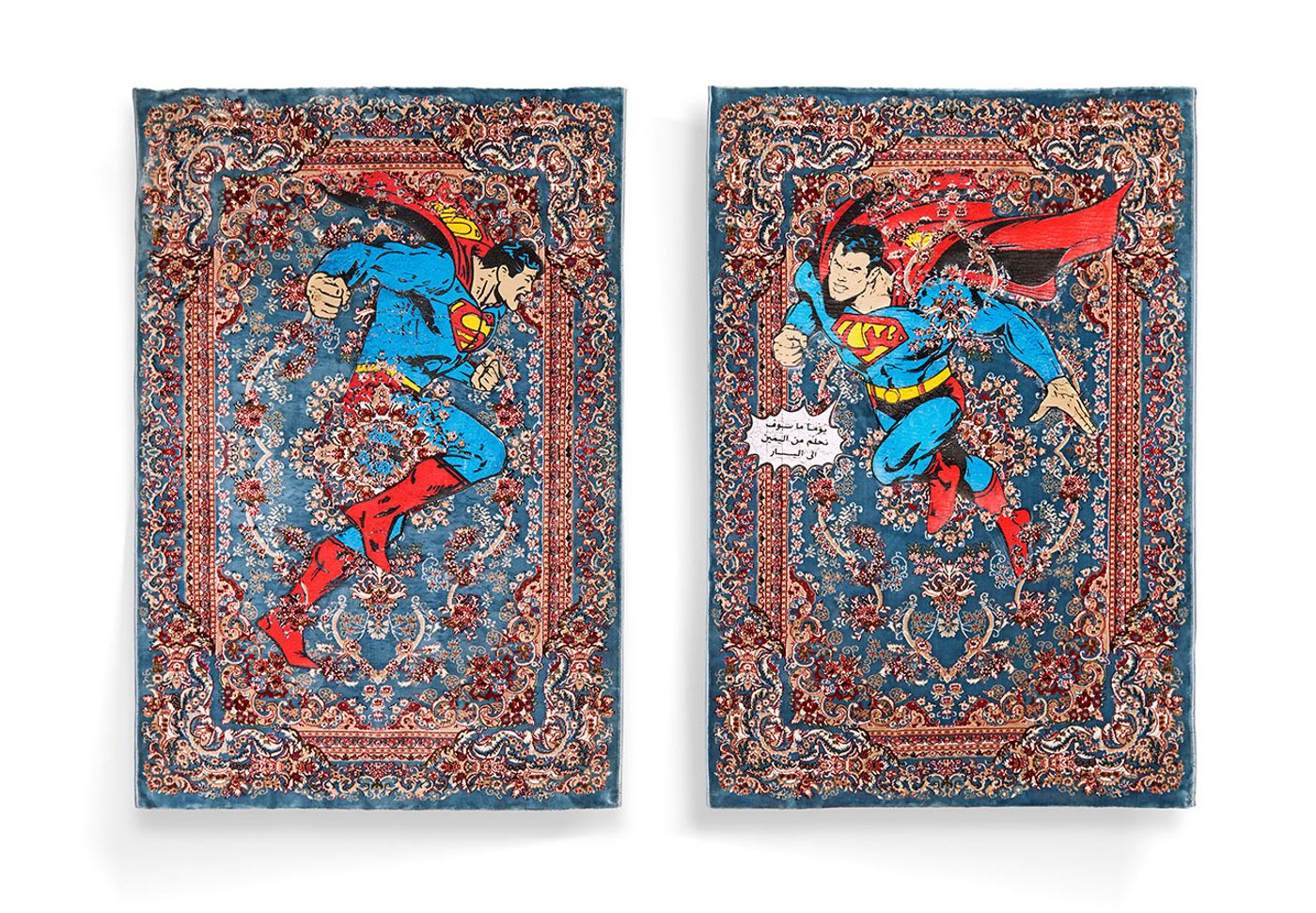

Lebanese-born, Kuwait-based artist Ali Cha’aban is as much a sociocultural commentator as he is an artist. He’s also fast emerging as a fashion photographer, shooting for Vogue Arabia and the Fashion Prize winners’ collections. Rich in pop culture references and steeped in nostalgia, Cha’aban’s multi-disciplinary projects harness the rich iconography of Arab culture in order to tackle socio-political issues such as the tension of today’s Middle Eastern identity and the predicament of the Arab diaspora, through a visual language that transcends language, religion and nationality. Whether he is superimposing superheroes onto Persian rugs, rephrasing famous rap lyrics, or creating a campaign for Nike, his primary aim is not to please his audience but rather to engage viewers in a productive discussion that transcends sectoral boundaries. Cha’aban talked to Yatzer about his artistic practice, his work as an art director and the challenges he faces as an Arab artist.

(Answers have been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Ali Cha’aban, The Confused Arab II from "RUGLIFE" series, 2016. Photo paper encased in plexiglass, 160cm x 130cm, Edition 1/5. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Ali Cha’aban in collaboration with Saudi Arabian designer Mohammed Khoja of Hindamme, The Arabic Dream series featuring Hindamme’s Fall 2017 collection, 2017. Photo by Rayan Nawawi.

Did you always want to be artist? What motivated you to become one and how did you get involved with art direction?

Actually my first years in college were focused on studying pre-med, but certain things that happened, like the war back in 2006 in Lebanon, detached me from that notion. I didn’t always want to become an artist. I was motivated by the need to comment on social and political events via visual representations which however evolved into wanting to become a storyteller of sorts. As an artist I like to create a ‘space’ for a model of dialogue that provides an opportunity to exchange ideas and notions, and foster discussions that transcend interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral boundaries. As artists, we are culture; we are the citizens of the world.

How did your background in anthropology influence your artistic sensibility?

Anthropology has catered to my needs, it helped me reflect the messages that I try to convey in my work. The method of creating a piece that impacts the viewer by creating an emotional attachment or resentment towards the piece of work is where anthropology functions; because it allows me to trigger a certain aspect in the viewer by knowing their way of thinking.

Ali Cha’aban and Rayan Nawawi, Satellite Culture, Nike x Vice magazine featuring Airmax97 model. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Ali Cha’aban and Rayan Nawawi, Satellite Culture, Nike x Vice magazine featuring Airmax97 model. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Ali Cha’aban in collaboration with Saudi Arabian designer Mohammed Khoja of Hindamme, The Arabic Dream series featuring Hindamme’s Fall 2017 collection, 2017. Photo by Rayan Nawawi.

In your work you often combine Western and Arabic cultural motifs and signifiers. Is this a reflection of modern Arab societies, caught between the seductive power of a global pop culture and the traditional cultural sphere dominated by Islam, or it is more reflective of your own upbringing?

To say the Arab Identity as a whole is shattered is a hyperbole. That emotion started to come alive within me around the start of the Arab Spring, seeing all these insurgencies and civil wars occur made me feel nostalgic towards a peace that never materialized. I believe that unity between the masses does not exist or is slowly fading through factions whether religious or ideological. I do believe however that there is an external influence on our identity that derives from the west, which I’ve discussed in my series “The Broken Dream” where I tried to familiarize myself with both sides of my upbringing.

Take us through the process of making “The Broken Dream” artworks. How did you come up with the concept and how time consuming is the process? Are you planning to expand the series?

The notion of the “Broken Dream” started with the idea of tackling the issue of neglected identity that seems to affect many of us. Many of my generation were able to relate to the struggle of late-found Arabism in a person’s life. I wanted to revisit an area of nostalgia known as inner-struggle, which is about indulging in other traditions without letting go of your own culture. This then brought forward the question of preservation: how does one consume so much from external influences and still have his/her identity in check?No, I’m not planning to expand this series. I’m going to put it on pause for a few years to do even more research into the topic of identity which will allow me to expand and develop this work more maturely.

Ali Cha'aban, My Imagination is no Longer Enough to Complete My Journey, 2017. Silkscreen on Persian carpet, 170cm x 120cm (Per Carpet) 170cm x 250cm (by Display). Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Ali Cha'aban, The Broken Dream II, 2017. Silkscreen on Persian Carpet, 220cm x 170cm. Photo © Ali Cha'aban.

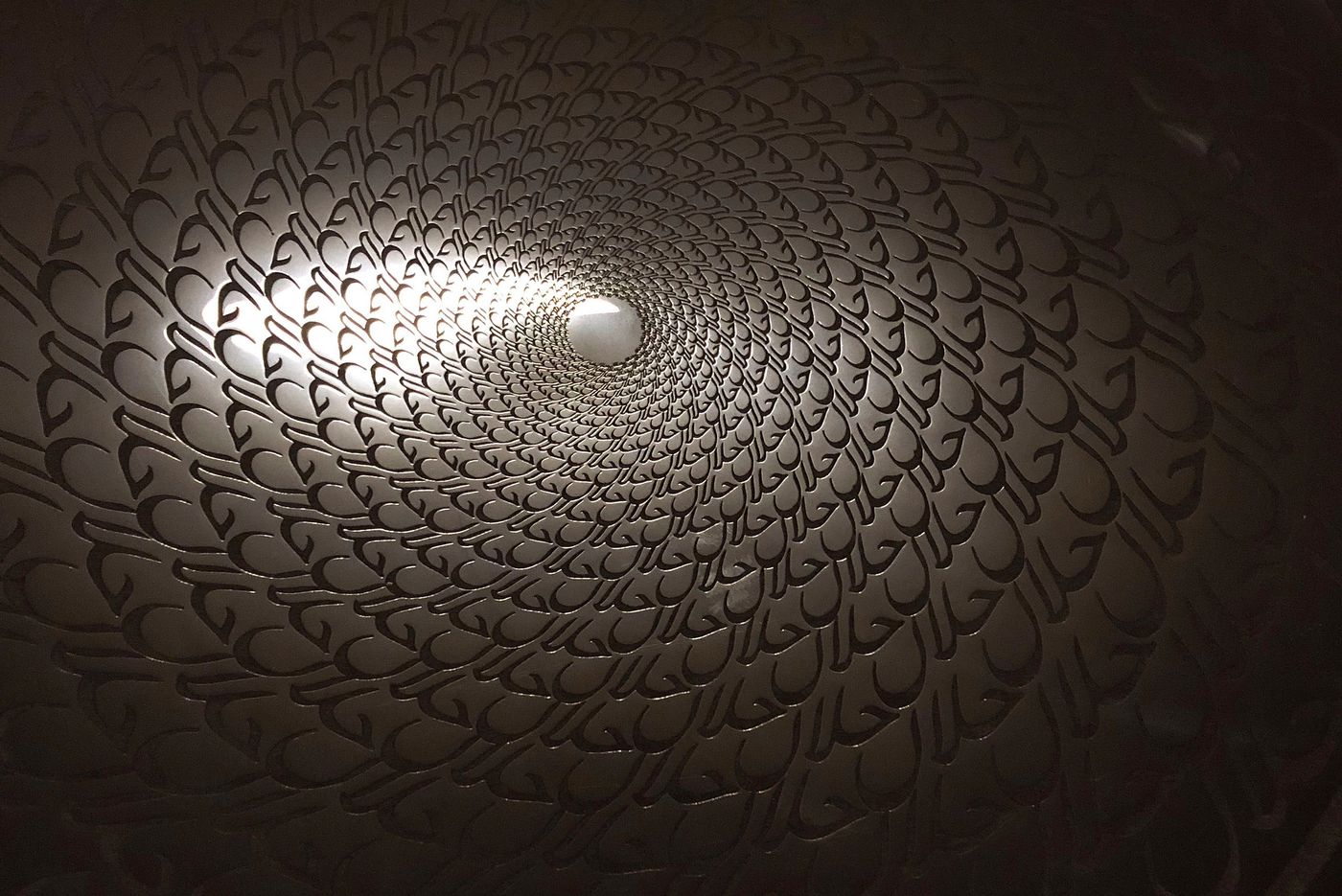

Ali Cha'aban, What’s halal my killer? What’s haram my dealer?, 2013. Digital print encased in Plexiglass, 125 cm circumference. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Ali Cha'aban, What’s halal my killer? What’s haram my dealer?, 2013. Digital print encased in Plexiglass, 125 cm circumference. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Why did you choose to depict Superman with bruises and Wonder Woman after a fall? What is the significance of both superheroes being in distress?

The point of this work was to explore an area of reality where the truth is always harsh; that is how I tried to signify the two. The cruelty of reality, I wanted to represent identity-crisis in a comic manner to ease the seriousness of that topic which is confronting cultural losses.

There is a strong current of nostalgia running through your work. What is its significance? Does it reflect a longing for the innocence of childhood and the simplicity of the pre-digital age, or is it a form of escapism from current socio-political problems?

My work can be simplified by ‘Hiraeth’ which is a Welsh word which means ‘nostalgia’, a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return or a home which maybe never was. Many refer to my work as dystopian, contrary to idealistic daydreams. To me art is a form of social-commentary that can highlight an issue or shed light on a subject matter. It’s a form of communication for an artist to address a concern and generate awareness. Maybe I long for a state of identity between the masses that will never be grasped, and that makes me idealistic, meaning I’m a walking paradox.

Ali Cha'aban in collaboration with 2d2cm, The “Efficiently illuminating your way” editorial for 2d2c2m. Photo by URBFITTER.

Ali Cha'aban in collaboration with 2d2cm, The “Efficiently illuminating your way” editorial for 2d2c2m. Photo by URBFITTER.

As an artist, conceptual considerations appear to trump aesthetics while the opposite is usually true in commercial art direction. Is there an optimum balance between the two? Do you calibrate their relationship for each new project?

As a contemporary artist, I consider myself belonging to the school of Marcel Duchamp, an art that serves the mind. Once we let go of the conviction that art should be aesthetically pleasing, we find ourselves in a place where the idea, concept or message is more important than the execution. It differs from one artist to another. I for one believe that the message is more important than the appearance. My work aims to provoke a thought or an emotion; to create a discussion which is generally achieved by disconnecting from visual beauty.In art direction I try my best to depict a scene or a story in my visuals. I believe photography is the best form of capturing a moment, but I still deal with my ‘scenes’ as an artwork which makes me believe I am becoming a renaissance man contradicting my earlier school of thought. But I have learned to disconnect and sometimes connect both schools when approaching every project.

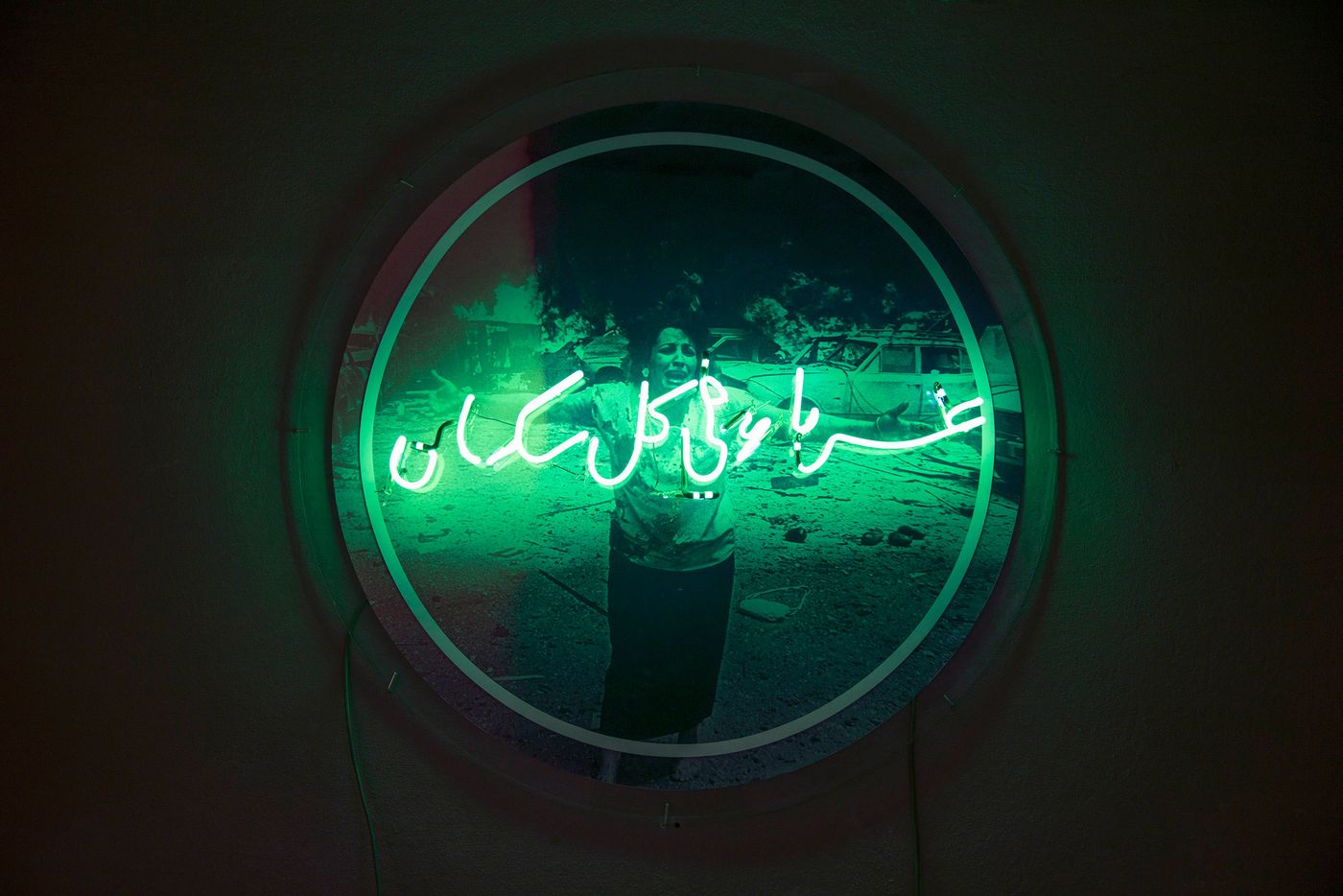

Ali Cha’aban, Strangers Everywhere from "refugee emotions" series, 2015. Poster print encased in plexiglass, neon installation, 125cm circumference. © Ali Cha’aban.

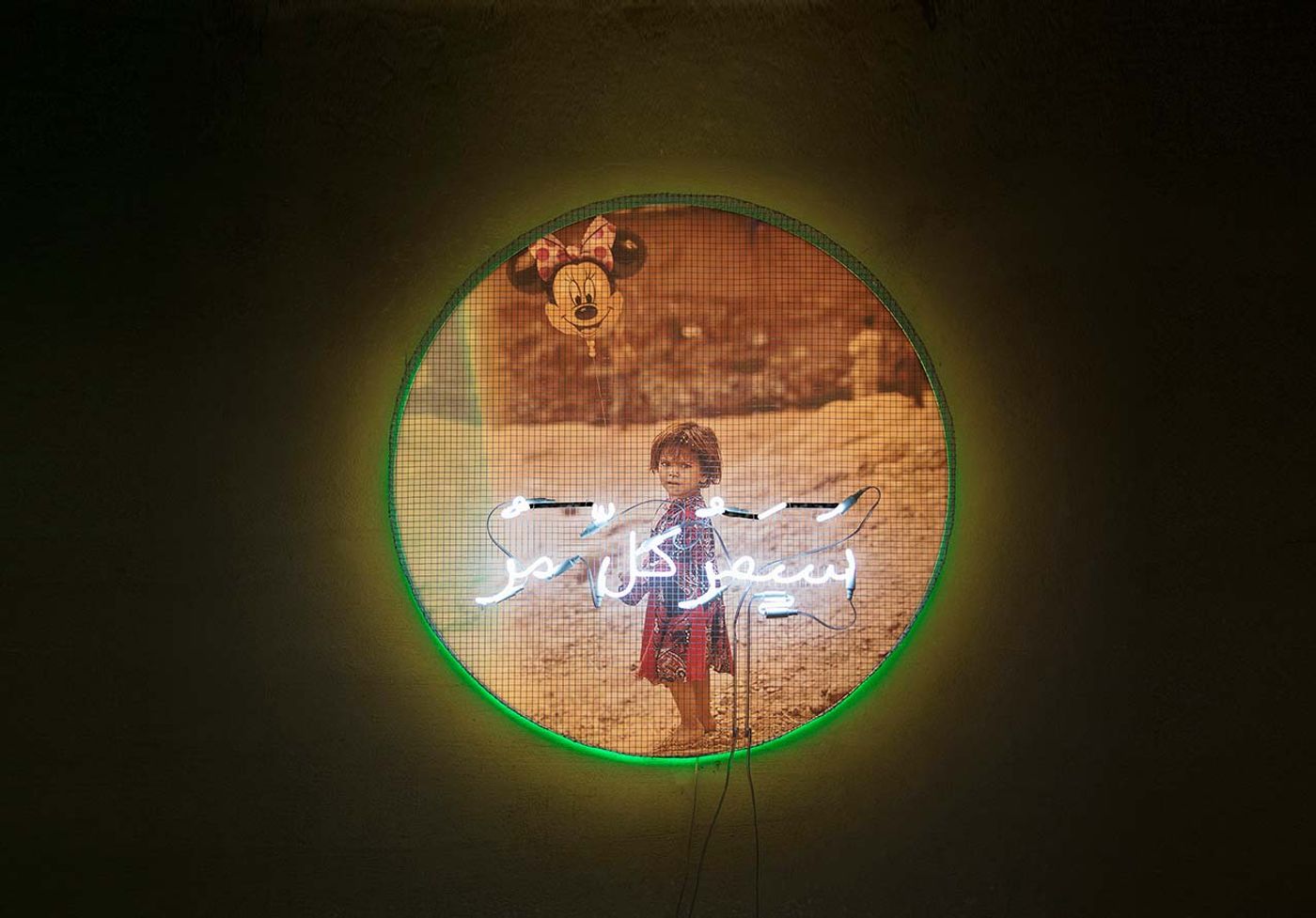

Ali Cha’aban, This Too Shall Pass from "refugee emotions" series, 2016. Neon on barbed wire fence, photo paper, lightbox installation, 125cm circumference. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.

Your work touches upon the dichotomy between people’s private life and the public sphere in Arab societies. Do you believe art can blur the boundaries between them and foster a furtive dialogue?

Art functions as a haven for ideas, art is propaganda, art is a voice, art is a means to seek change. It’s a form of communication that goes beyond normal discourse, it has the ability to propel an idea from being talked about to being perceived. Many artists seek art to voice their opinion in a world that is very problematic. In the age of social media the need for art is crucial to prompt people to take the appropriate action and to connect the masses under one model of thought.

In the Arab world, national, sectarian and religious identities seem to be both antagonistic and complimentary concepts. What kind of identity are you trying to forge through your art?

It’s a long stretch but I’d like to “unshatter” these shattered identities. But I don’t believe I have the power to “unshatter” that dogma; as I said art is a form of social awareness, it helps raise an issue with the public in the hope of sparking a reaction. That reaction is where change occurs.

What are your working on right now? Are you planning any new projects?

I’m collaborating with a fellow Saudi Arabian artist, Khalid Zahid. We’re working on an installation series that explores the concept of metaphysics, a branch of philosophy that explores abstracts concepts such as being, knowing, identity, time and space, and its relation with modern-day Islam.

Ali Cha’aban portrait. Courtesy of Ali Cha’aban.