Pencil on Paper: The Visual World-Making of Maria Kriara

Words by Eric David

Location

Pencil on Paper: The Visual World-Making of Maria Kriara

Words by Eric David

“Greetings to you, whoever you are! We come in friendship to those who are friends.” This is the audio message, spoken in ancient Greek and repeated in a loop, which greeted visitors to Greek artist Maria Kriara’s recent solo exhibition The Pawnshop at Can Christina Androulidaki Gallery in Athens. Sourced from the interstellar messages that, along with other sounds and images portraying the diversity of life and culture on Earth, the Voyager spacecraft has been carrying out in space for 40 years now, it perfectly encapsulates Kriara’s artistic proposition: the use of past ephemera, be they images that she has meticulously recreated in photorealistic pencil drawings or text fragments that she has pieced together, to create representational narratives that speak about nostalgia, memory, and our contemporary mythologies. Yatzer talked to the artist about her latest project, her rewards as an artist and her latest solo show.

(Answers have been edited for brevity.)

Maria Kriara, Untitled(detail), 2014, Drawing, Pencil on paper, 80x120cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

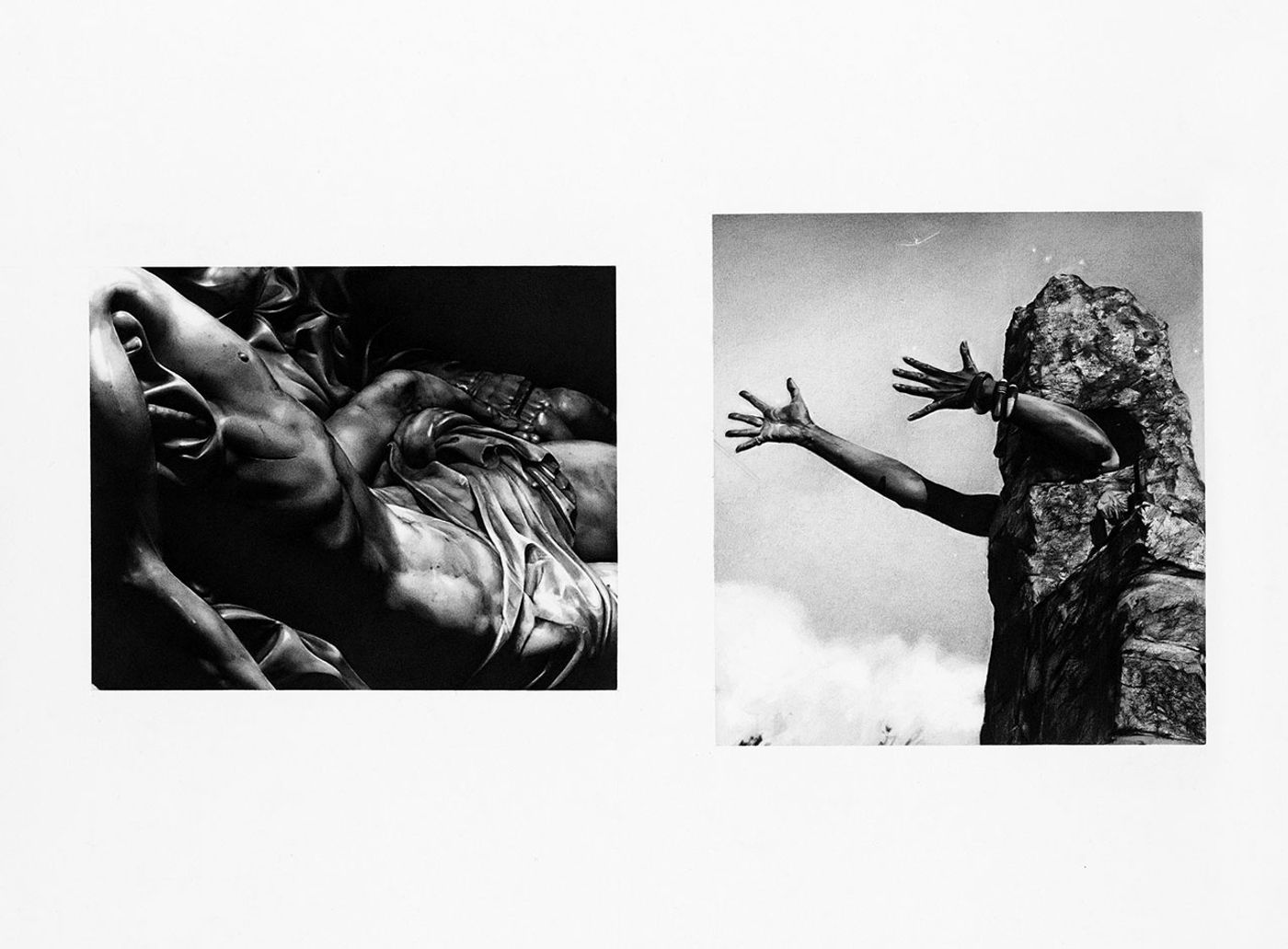

Maria Kriara, The Crack, 2017, Pencil on paper, 35x50cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, The Crack, 2017, Pencil on paper, 35x50cm, detail. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

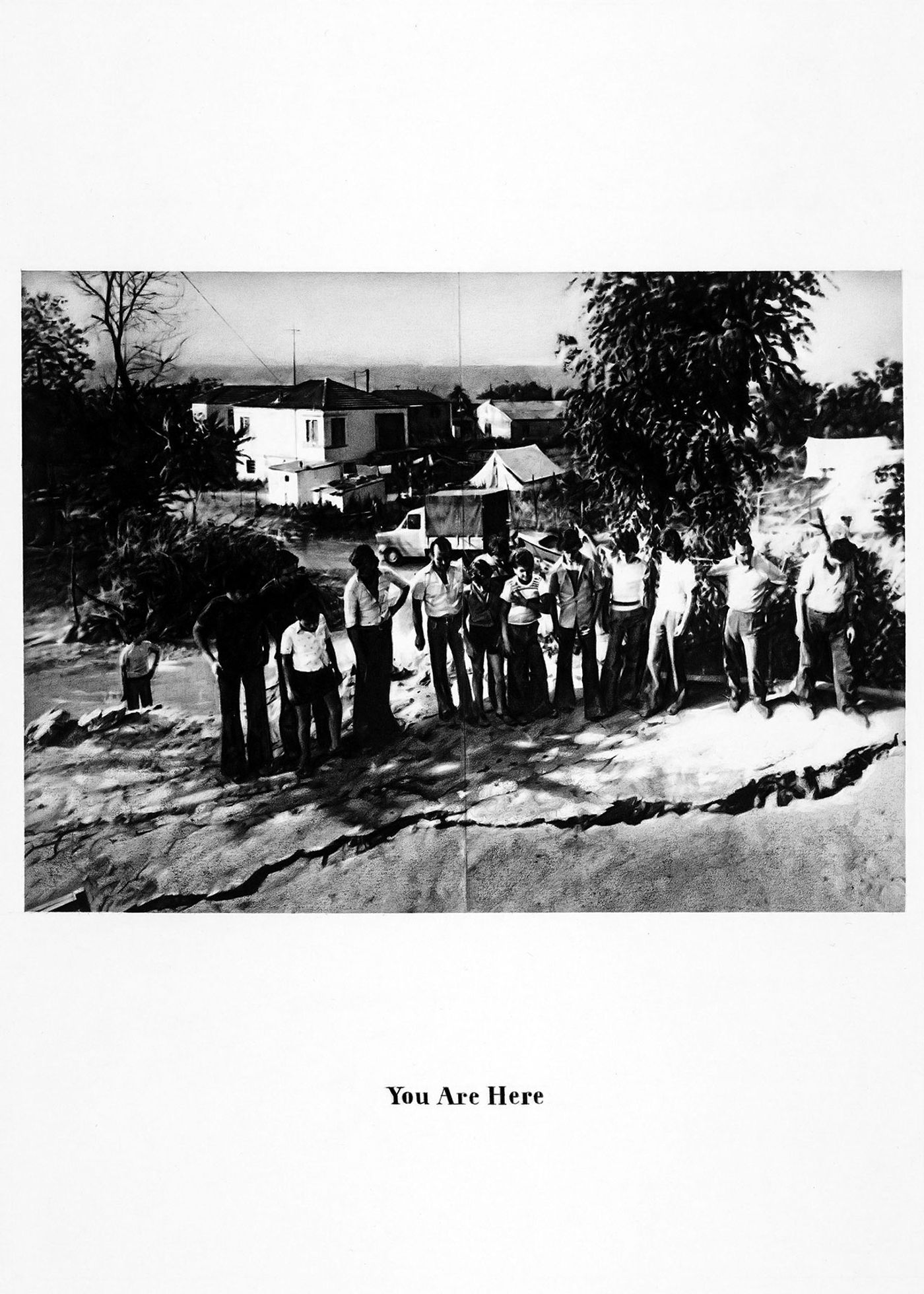

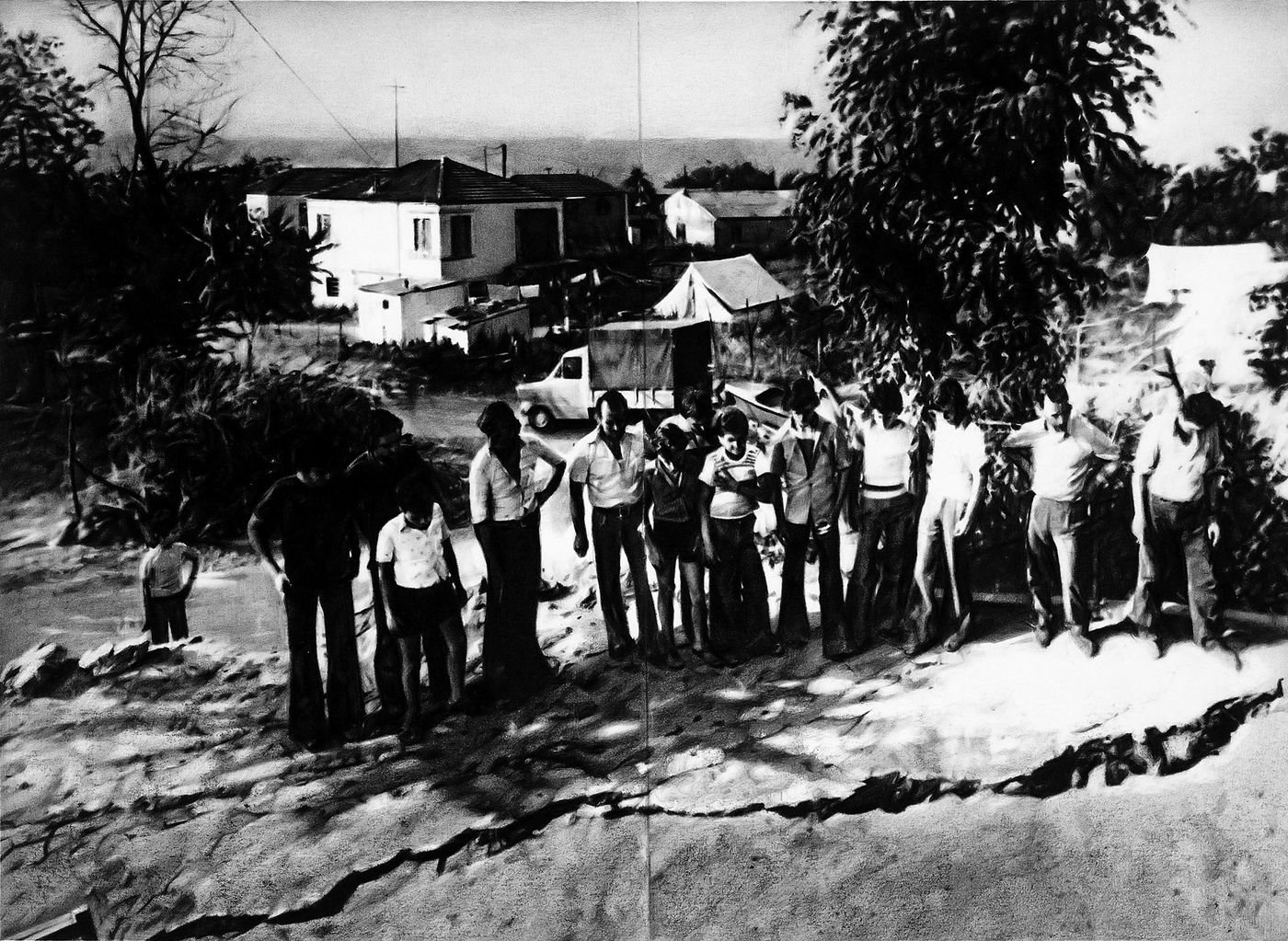

Maria Kriara, Per Aspera Ad Astra / Από Τις Κακουχίες Στ'Αστέρια / Through Hardships To The Stars, 2017, Silkscreen print on Olin paper 224gr, 50x65cm, Ed.10. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

What is your motivation as an artist? Who or what inspires you?

I wish I could prove to be more enlightened regarding this question, but, actually, my motivation as an artist is the capacity of being an artist. It’s been an essential part of my self-constitution. Painting has always been what interested me the most, followed by history of art and ideas, together with the body of images and stories one encounters when digging into the collective cultural deposit. So, I do it out of necessity, anxiety, and some sort of cultural kleptomania, I suppose.

Maria Kriara, Untitled (detail), 2014, Drawing, Pencil on paper, 80x120cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

What part did your architectural background play in you becoming an artist and how does it inform your work?

The years of my studies were very formative, especially considering the fact I never really aspired to be an architect. However contradictory it may seem, I gained confidence as an artist to a great extent due to architecture. I could make a long list, but if I were to single out the most precious of all lessons that architecture has taught me, that would be the importance of taking a step back, and the ability to speak about my obsessions in an impersonal tone.

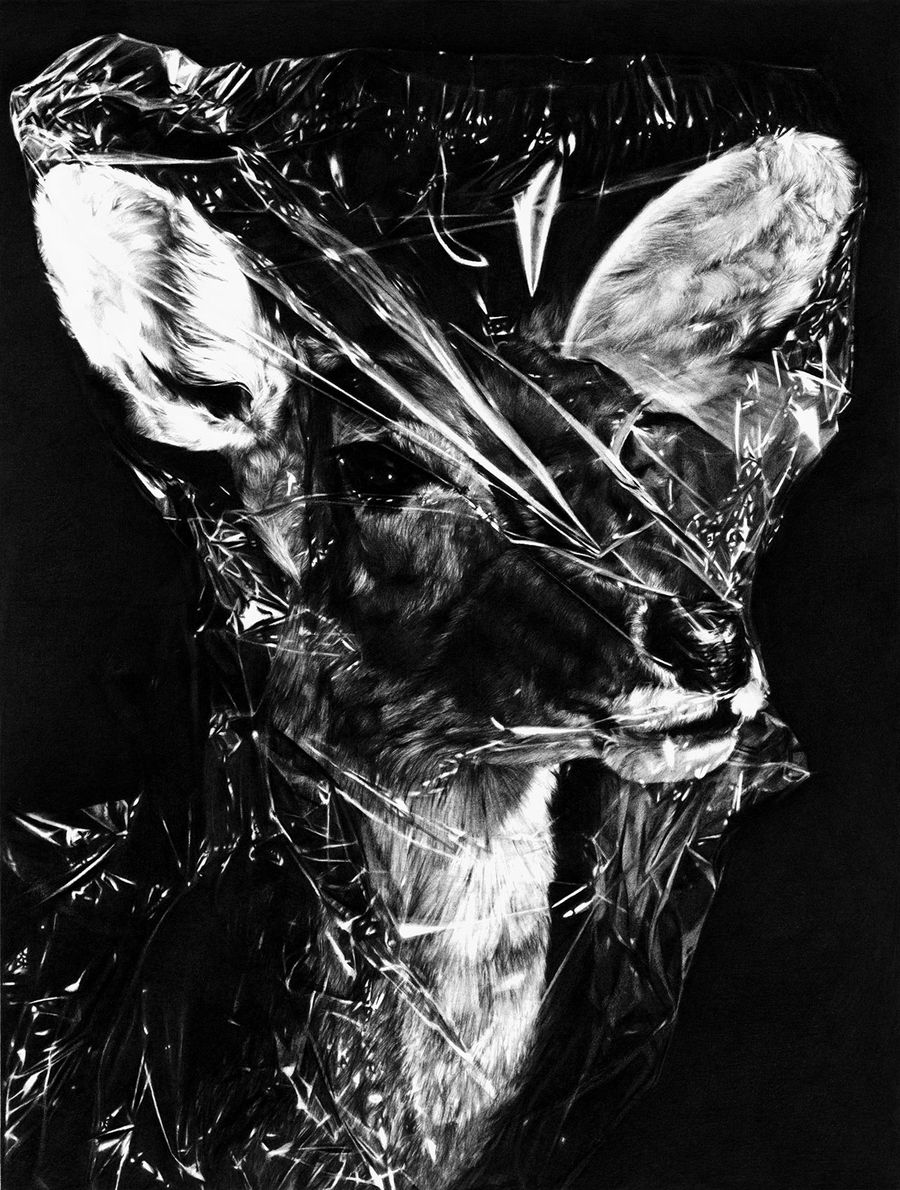

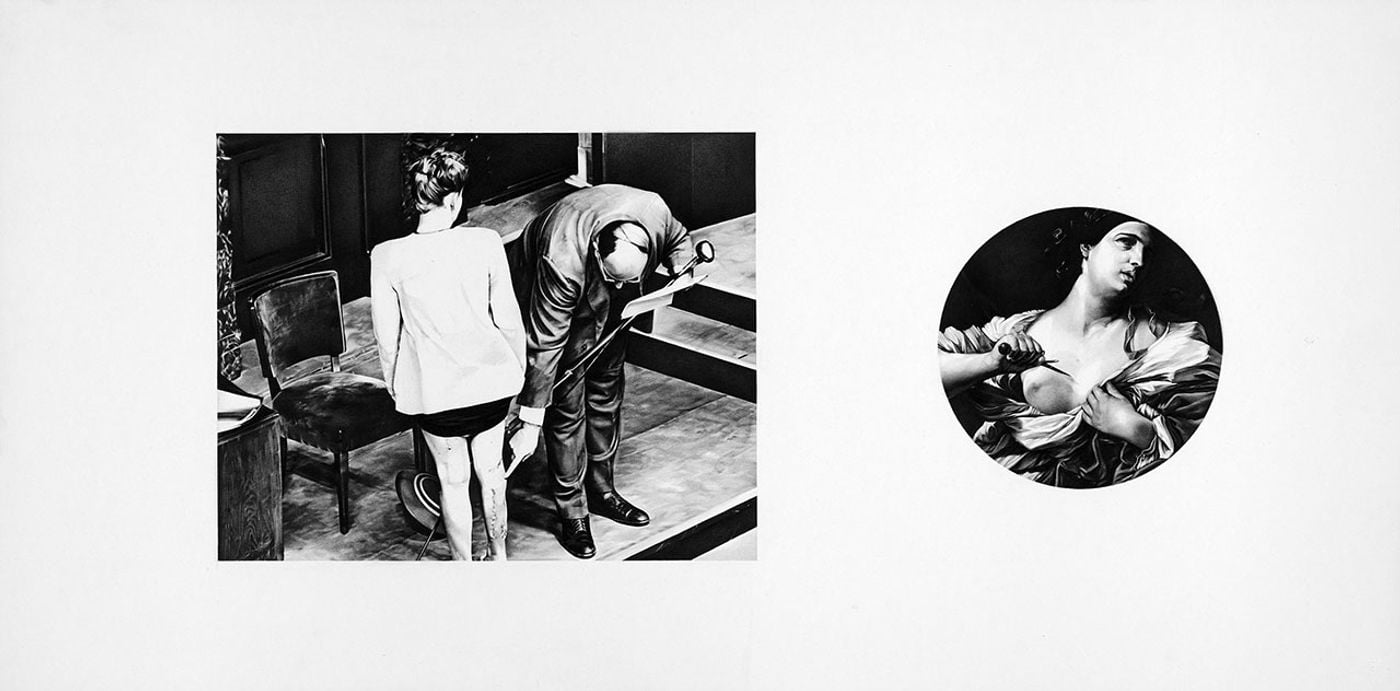

Your pencil drawings exhibit extraordinary technique in their photorealism. Why did you choose to work in this medium?

Probably because, among other means of representation I’m familiar with, drawing is the one that best serves both the accuracy and the specific anti-gestural quality I’m trying to attain. Besides, the pencil is a very common and basic tool, the minimum technology required to structure an image; both graphite’s texture and color have nothing spectacular about them, they have a certain modesty, which is pretty much what I am looking for as well.

Maria Kriara, Per Aspera Ad Astra / Από Τις Κακουχίες Στ'Αστέρια / Through Hardships To The Stars, 2017, Silkscreen print on Olin paper 224gr, 50x65cm, Ed.10. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, Enduring Ephemera (pp.27-34), 2016, Sanded newspaper pages, 72x59cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, Enduring Ephemera (pp.27-34), 2016, Sanded newspaper pages, 72x59cm. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

How strenuous and time consuming is the process of drawing in such extraordinary detail? Is there a reward, practical, spiritual or otherwise, for you as an artist for creating works of such excruciating labor?

There are numerous, pretty uneven moods that gradually occur throughout the process, which vary from Zen-like to being obsessive or even compulsive; because, as you suggested, the making of these drawings does indeed demand a high amount of concentration, precision and patience. But, of course, in several stages pleasure is very much involved, too. The purpose of engaging in this elaborate process, however, is rather irrelevant to a manifestation of draughtsmanship, or being praised about my endurance. Reward comes after my work has finished and the drawings leave the studio, when I can really test whether they have the capacity to achieve an effect, which may be empirical, emotional, aesthetic, intellectual… even physical if possible.

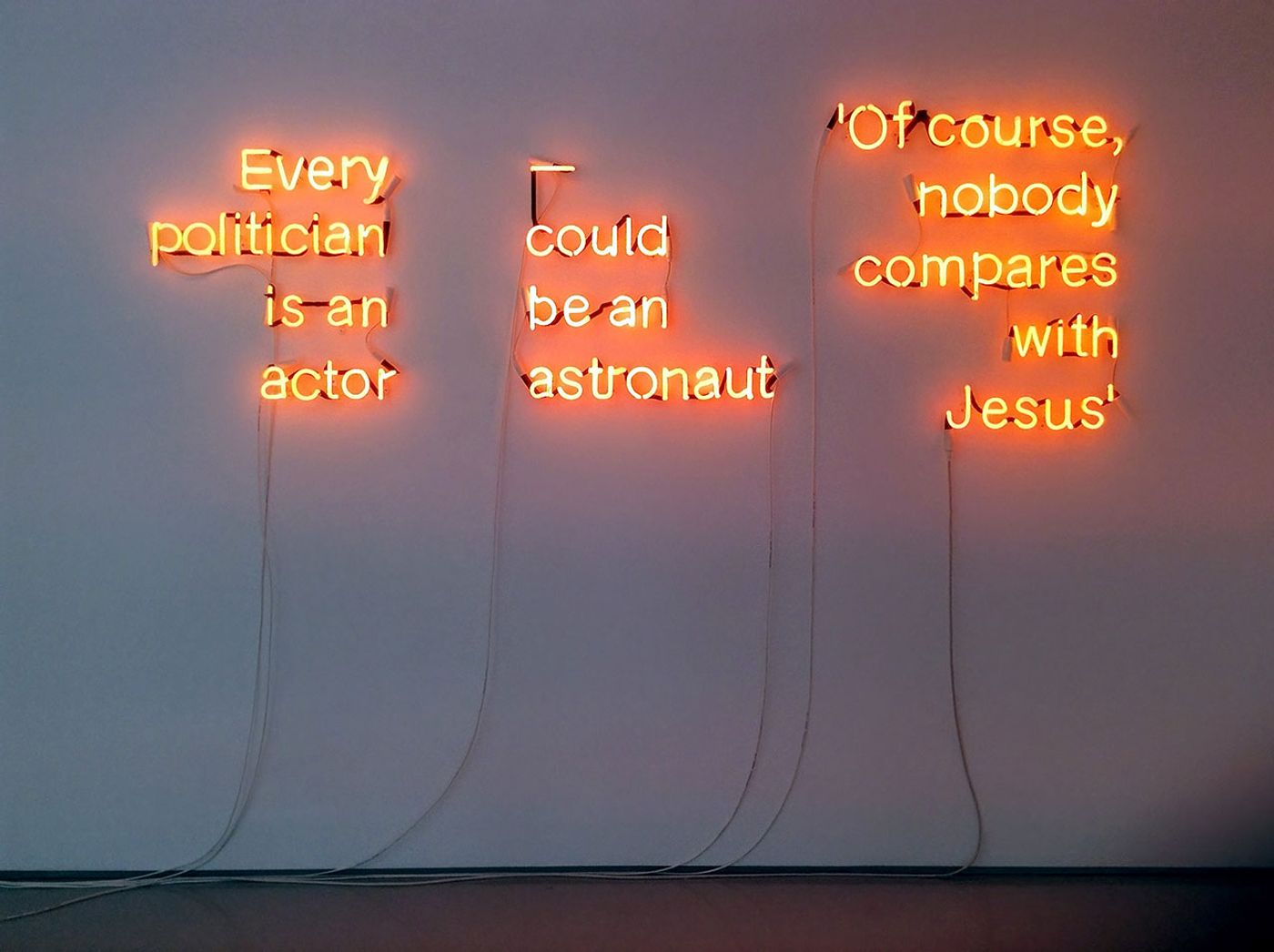

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2017, Neon Light, ap.210x70cm, Unique. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

The images in your work have a nostalgic quality, both in terms of subject matter and aesthetics, but they also seem very personal, as if they were discovered in some family’s attic. Where are they sourced from? What is the purpose behind their recontextualization and what part does nostalgia play in your work?

My sources vary according to the original purpose each image was supposed to serve. The ones I have used so far were largely obtained from art publications, museum digital collections, popular magazines, science books and historical records, the majority of which date from the early modern and expand to around the late modern period and the early 60’s ―which possibly justifies the nostalgic quality you described.

Nevertheless, concerning whether nostalgia played a role in my work, well, very recently it actually did. In my latest project at the Can Christina Androulidaki Gallery-a solo exhibition titled “The Pawnshop”-nostalgia held a prominent place, even if my intention wasn’t exactly to shower it with praise. The show’s starting point rested upon the fact that over the past almost 9 years of the crisis in Greece, pawnshops have started to appear more and more frequently in the city centres, emerging as a dynamic heterotopia. Having taken into account that the very moment a certain object passes through a pawnshop’s threshold it is immediately stripped off its previous connotations and turns into a commodity that is being reevaluated almost strictly according to, either it’s material value, or it’s utilitarian capacity, I wanted to provoke speculations around the status nostalgia, memory, and our contemporary mythologies can hold within such a context; what could remain, for example, out of a military decoration or a family heirloom’s previous attributes. Subtly however, through the pretext of a metaphorical pawnshop, the show attempted to also raise a different question; that of what is worth keeping.

Regarding the recontextualization you mentioned, visual fragments can demonstrate an impressive coherence, and by folding them out of their original sources and bringing them together onto equal ground, I attempt to increase the cultural load they are tied to, multiply their narrative capacity and stimulate new interpretations of them as a unified whole, in order, ultimately, to reactivate their aura, and create an experience that would have a certain impact, such as the ones I listed before in answer to your previous question.

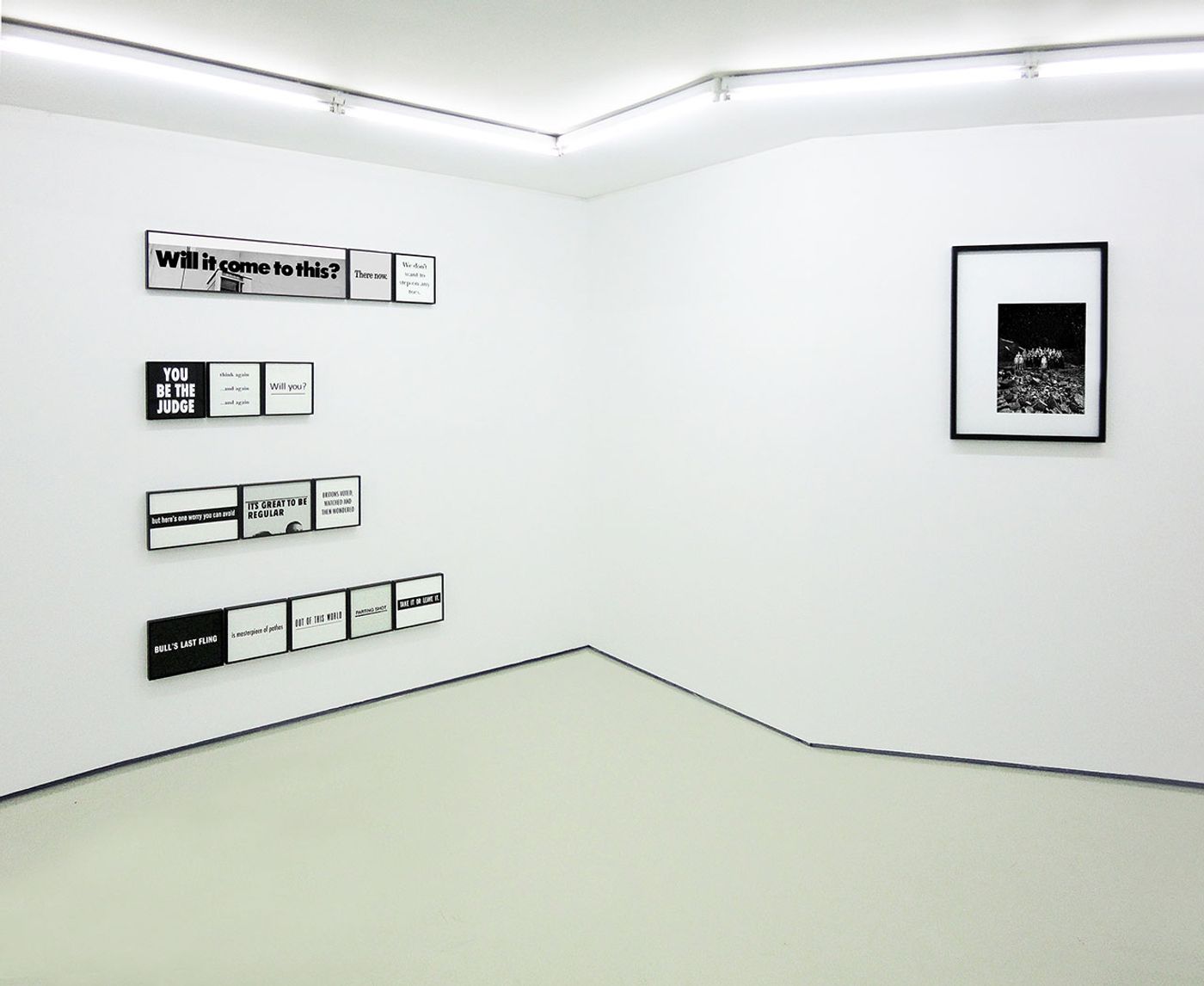

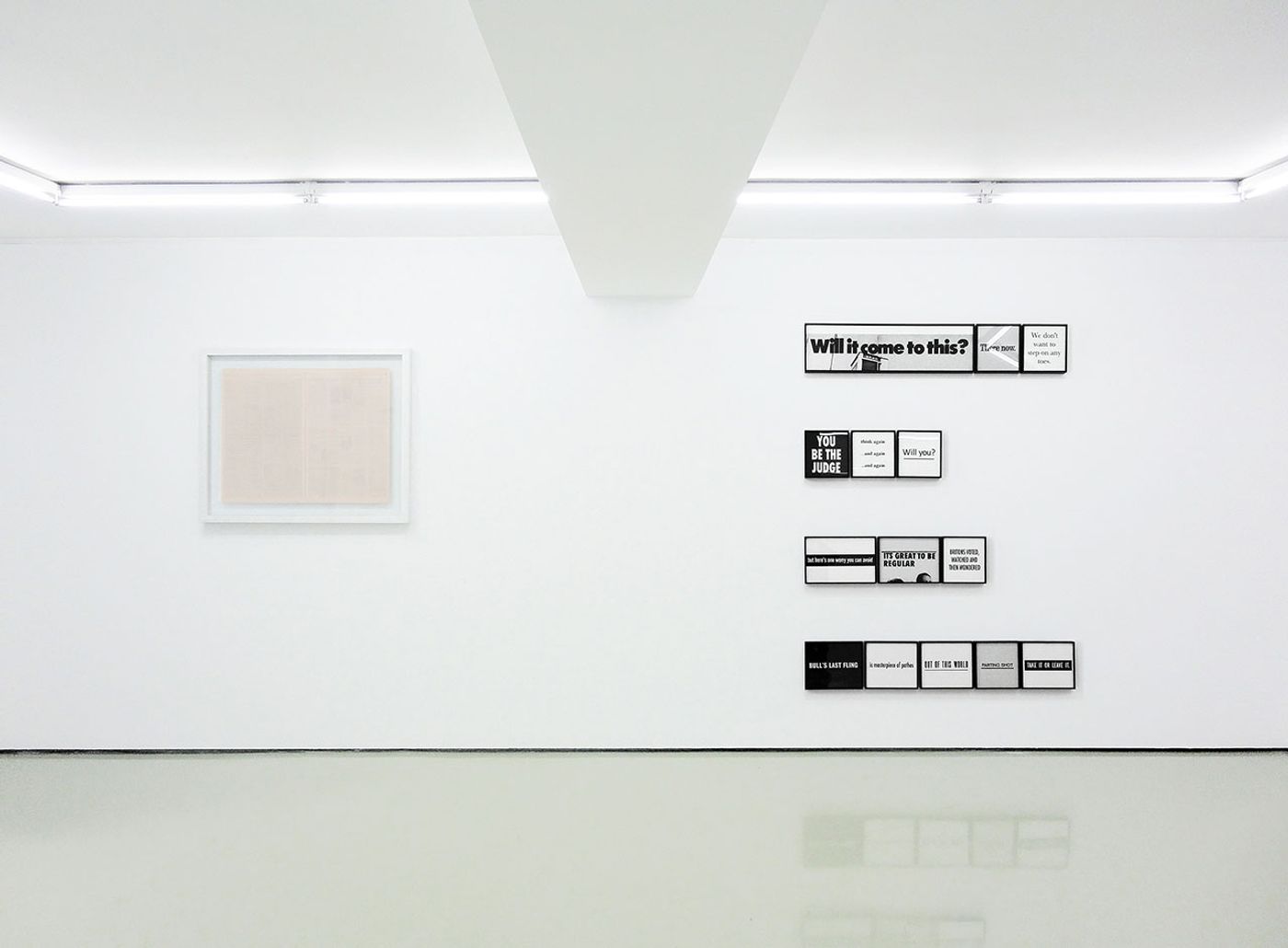

Maria Kriara, The Pawnshop, Installation View. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

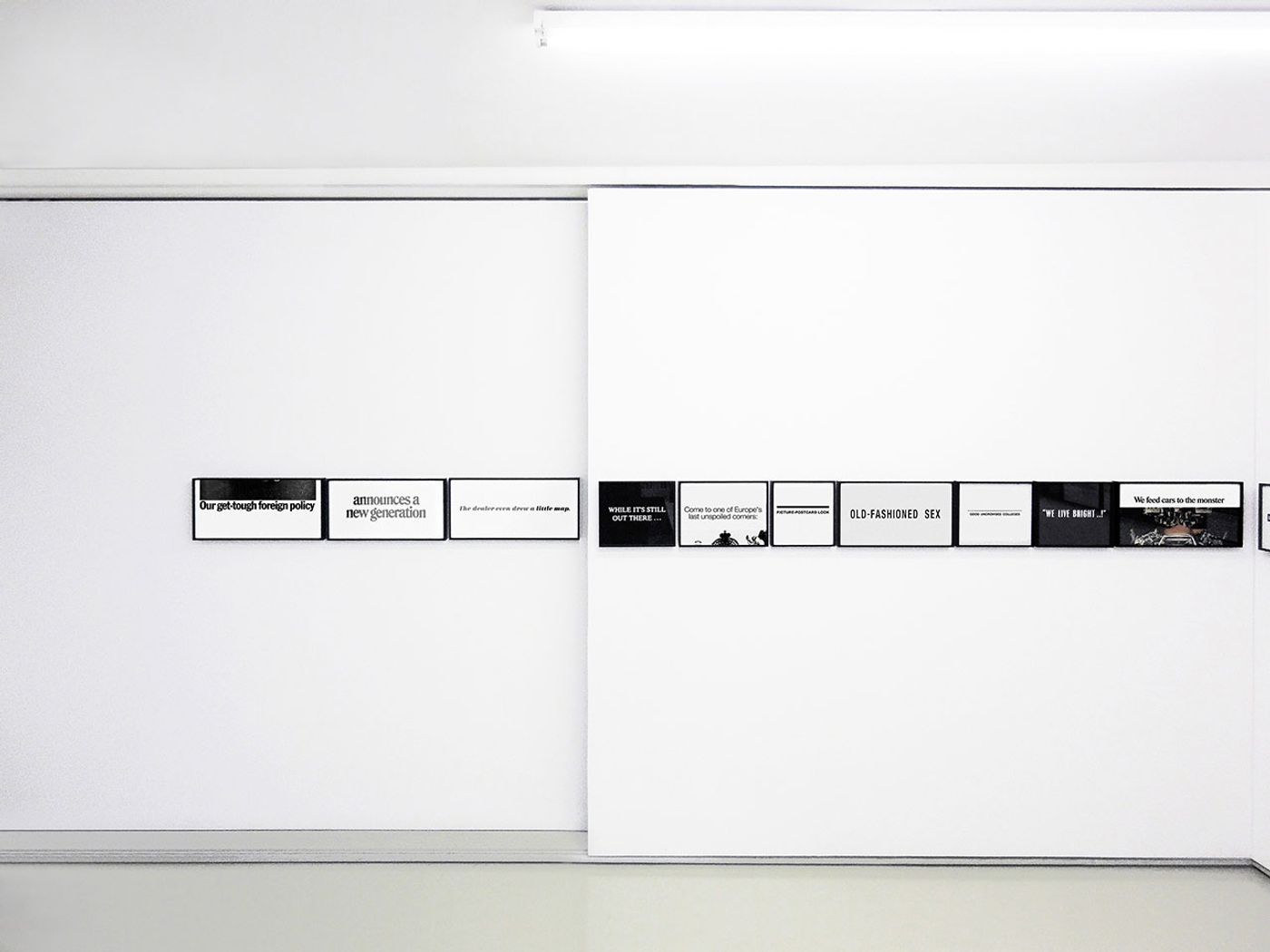

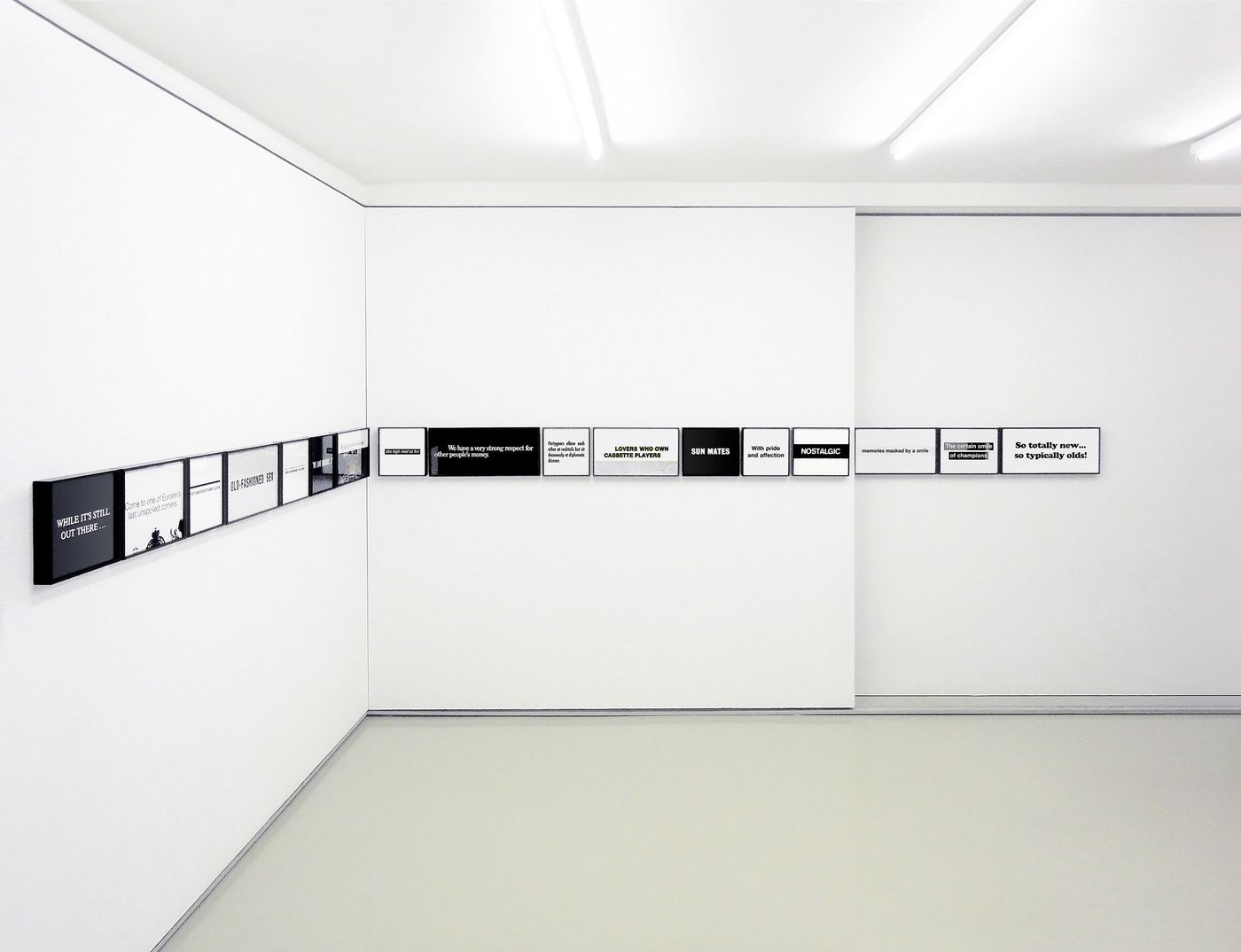

Maria Kriara, Our Get-tough Foreign Policy, 2017. Print on Matt Photographic Paper, dimensions variable, 600x20cm, Ed.3. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, Our Get-tough Foreign Policy, 2017. Print on Matt Photographic Paper, dimensions variable, 600x20cm, Ed.3. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

In your latest exhibition you have presented a series of text-based works. How did these come about and how do they fit in with your drawings?

The works that feature fragments of text were largely concept-specific, and part of them had a lot to do with certain linguistic tics, which have occurred within the frame of vernacular language and mainstream media. Moreover, the process both the neon sign and the friezes of text descend from, is very relevant to the one I described earlier about the drawings which contain several images, since the phrases used, were all found in old popular magazines and newspapers, and then cut and rearranged in series. In a sense, I somehow wanted to do my version of Brecht’s poem “A Worker Who Reads History”, having instead a fictional pawnbroker read the news in past ephemera, but more in the way of Max Ernst’s automatic writing in his collage novels and verbo-visual works.

You have mostly refrained from giving titles to your drawings, preferring instead to label them “untitled”, as opposed to your work that features text. Why is that?

When it comes to drawings, the truth is that I usually don’t think through titles, perhaps due to some sort of defense strategy―to prevent the drawings from being perceived as illustrations to a specific concept. But, also, because I consider them unnecessary or too much, especially for the drawings that feature more than one image, unless the title, either functions as a citation, or in the case that it was originally conceived before the visual part had taken any kind of form in my head.

Maria Kriara, Our Get-tough Foreign Policy, 2017. Print on Matt Photographic Paper, dimensions variable, 600x20cm, Ed.3. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, Our Get-tough Foreign Policy, 2017. Print on Matt Photographic Paper, dimensions variable, 600x20cm, Ed.3. Courtesy of CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery and the artist.

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2012, pencil on paper, 60x120cm.

You have been presenting your drawings in pairs, triads or tetrads as well as making collages out of separate phrases. Is there an overreaching narrative that the viewer is invited to deduce or fabricate from these pictorial and textual compilations?

Admittedly, I’ve spent a lot of time doing research around the images I’ve chosen to join together, their origins, their interconnection, the potential common side stories or the visual kinships between them. However, if I do acknowledge the importance of suggesting a certain meta-narrative quality or a specific framework regarding the works―and this applies to both drawings and the works using text―I usually choose to do so through the title, or a concept as general as that of a solo show. Other than that, I often consider my own interpretations that have resulted in each of this works, almost irrelevant to the viewer, because, personally speaking, I find it both difficult and sort of annoying to be honest, to grant myself, as an artist, the position of a modern sphinx.

What are you working on right now?

I’ve been pretty busy lately. I’ve just completed some more works that feature text, and as we speak, in order to give you an overall impression, my studio is being filled with dolphins, mountains, tigers, icebergs, seascapes, anatomy manuals, Renaissance paintings, and many more images, separate, merged or superimposed upon each other, most of them in progress, and waiting for me to finish off drawing them.

Maria Kriara, Untitled (detail), 2012, pencil on paper, 60x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled (detail), 2012, pencil on paper, 60x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2012, pencil on paper, 60x120cm.

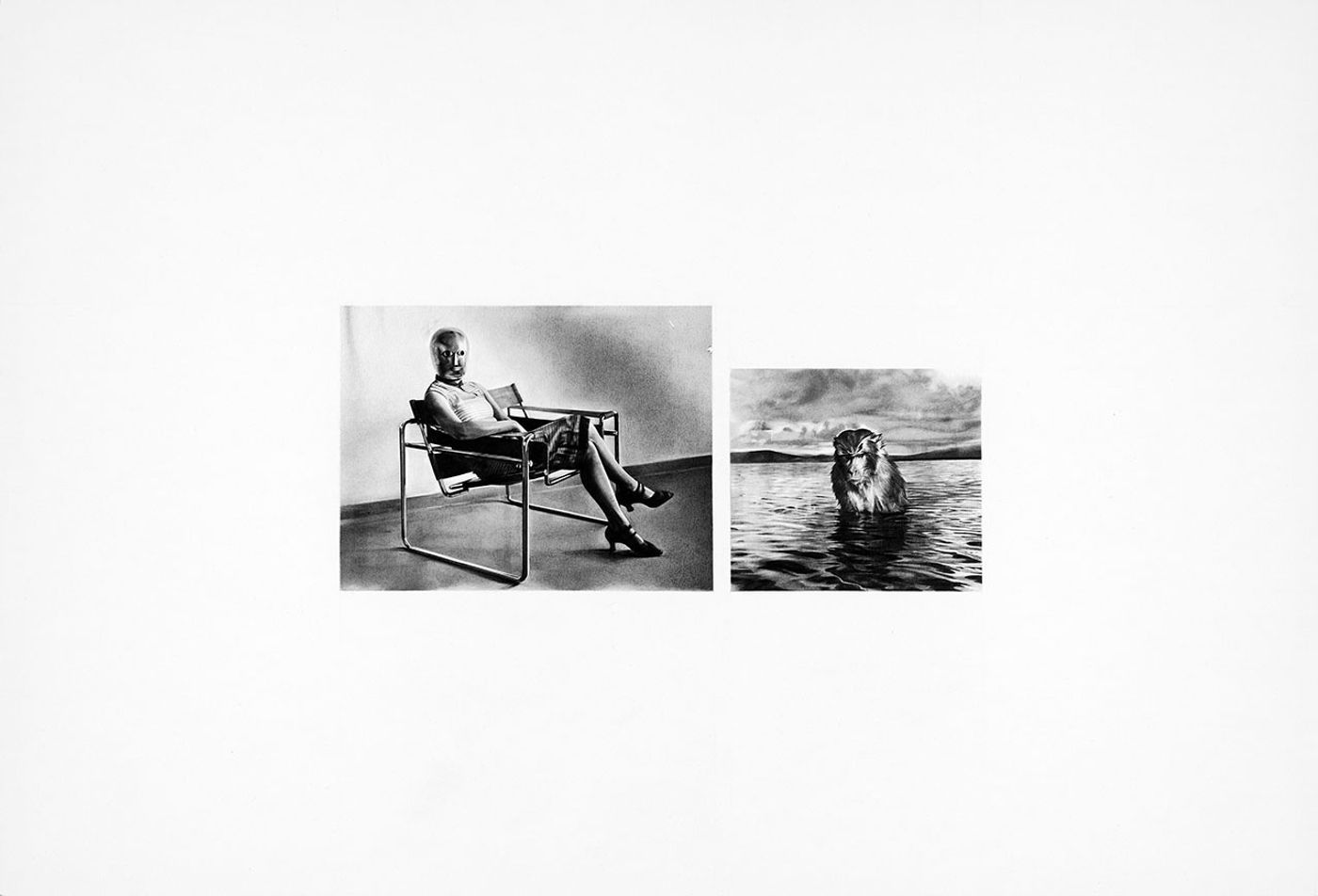

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2013, pencil on paper, 60x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2013, pencil on paper, 55x80cm.

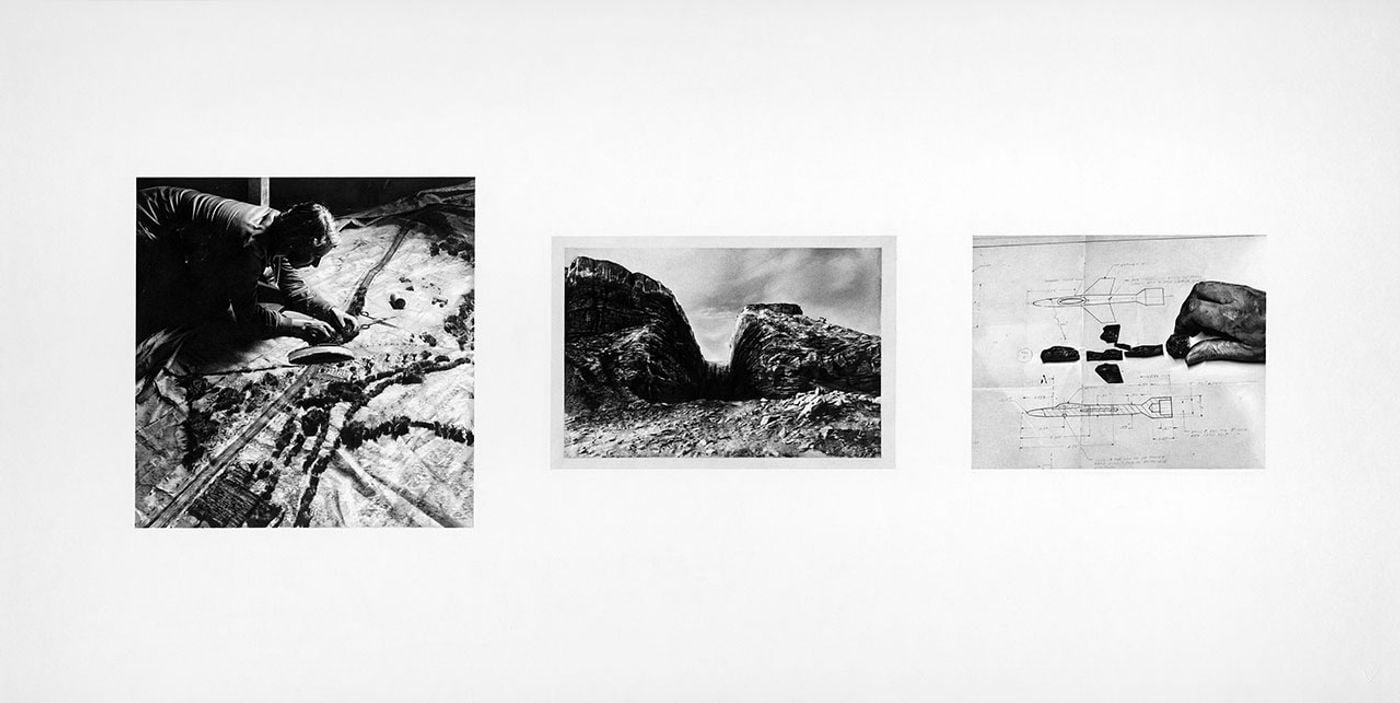

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2014, graphite on paper, 60x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2014, graphite on paper, 80x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled (detail), 2014, graphite on paper, 60x120cm.

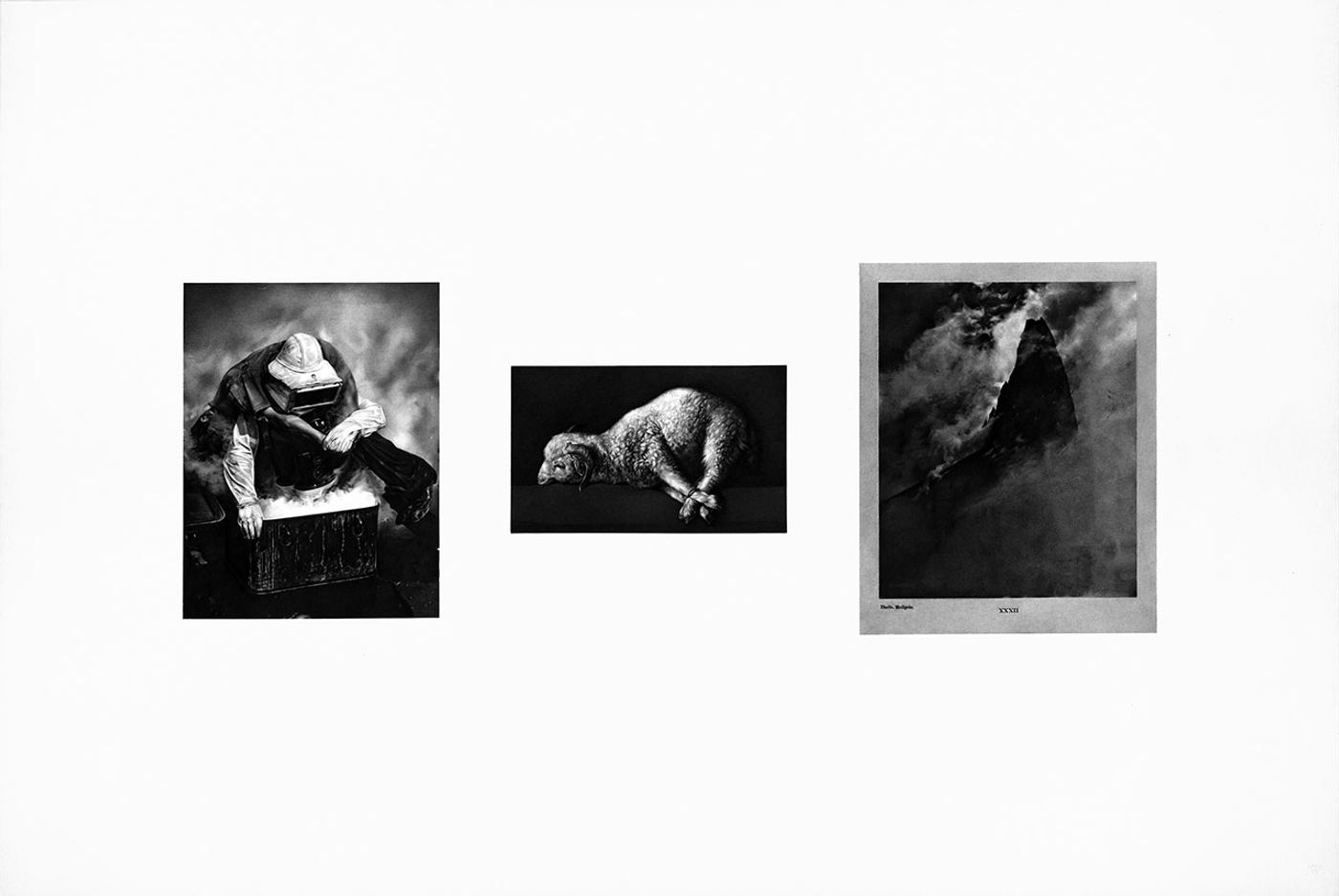

Maria Kriara, Untitled, 2014, graphite on paper, 80x120cm.

Maria Kriara, Untitled (detail), 2014, graphite on paper, 80x120cm.

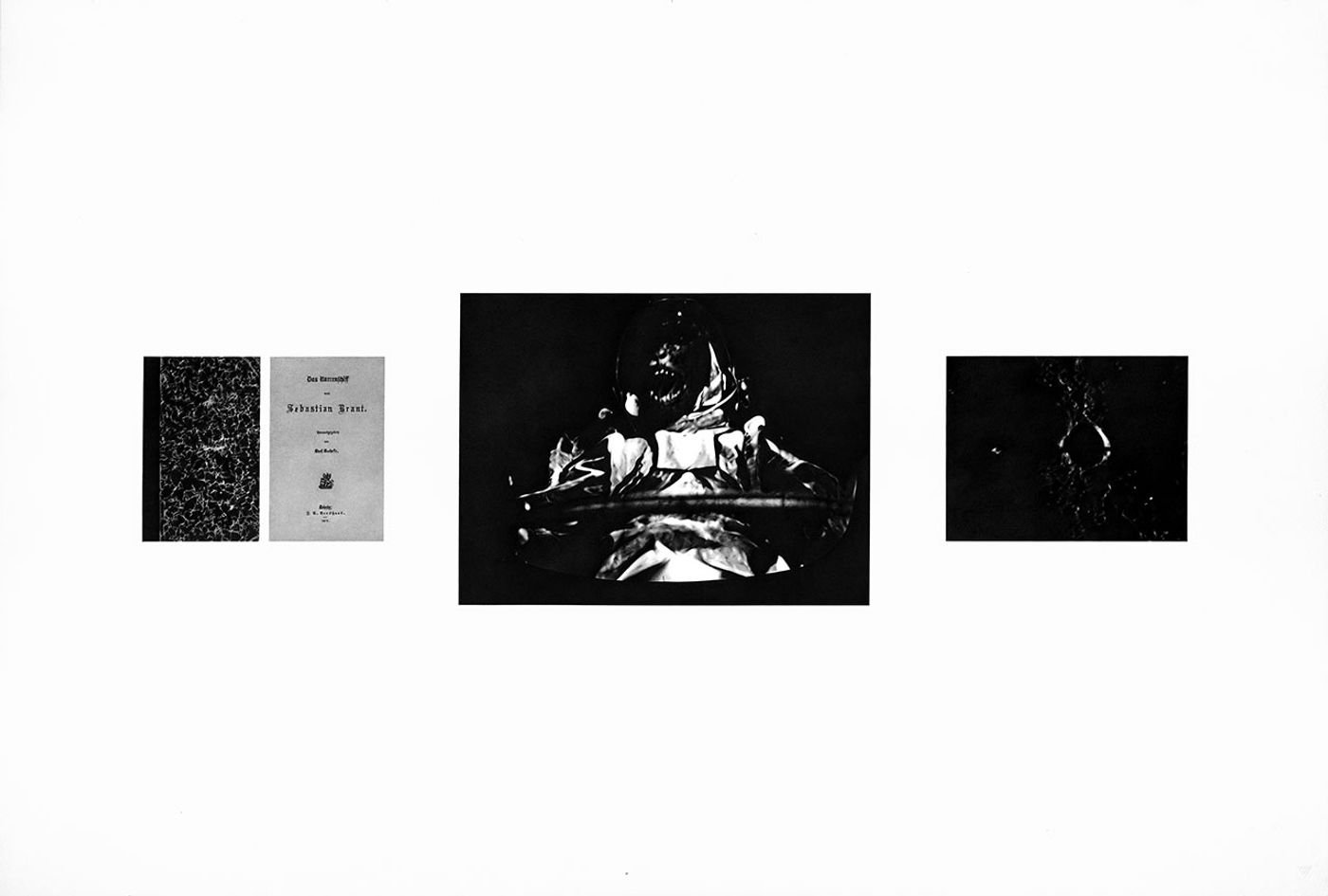

Maria Kriara, Study for a Ship of Fools, 2014, graphite on paper, 80x120cm.