The Art of Collage: Rodrigo Torres’s Assembled Universe

Words by Alexander Mordoudack

Location

The Art of Collage: Rodrigo Torres’s Assembled Universe

Words by Alexander Mordoudack

There is something inherently optimistic in the construction of art, at least in as much as it expresses the conviction that a meaning is worth representation, and that meaning is a valid projection in and of the future. Collage is a very special way of making evident this process of optimism in its own form. For Rodrigo Torres, “collage symbolizes a very direct way to reorganize the world”. In that phrase, his own identity as an artist comes through. Torres is direct, effortlessly humorous and meticulous in his reorganizing of his surroundings. While his collages, including a celebrated treatment of banknotes from around the world, have brought him recognition, his body of work as a whole is just as thoughtful. On the occasion of his participation in Miart last month, we discussed the above, and revisited some of his earlier work, all the way through to his present explorations.

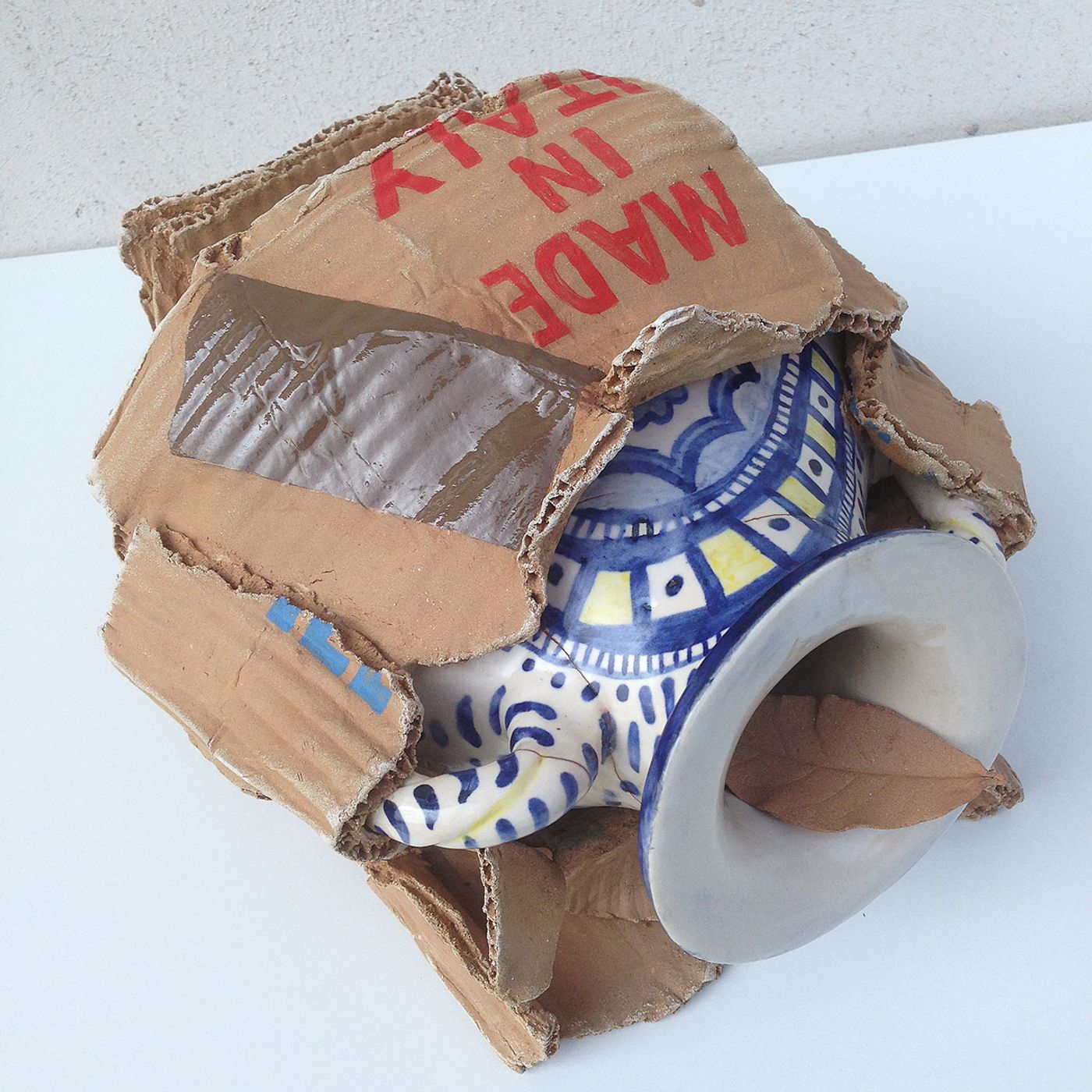

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 27.9 × 15.2 × 15.2 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

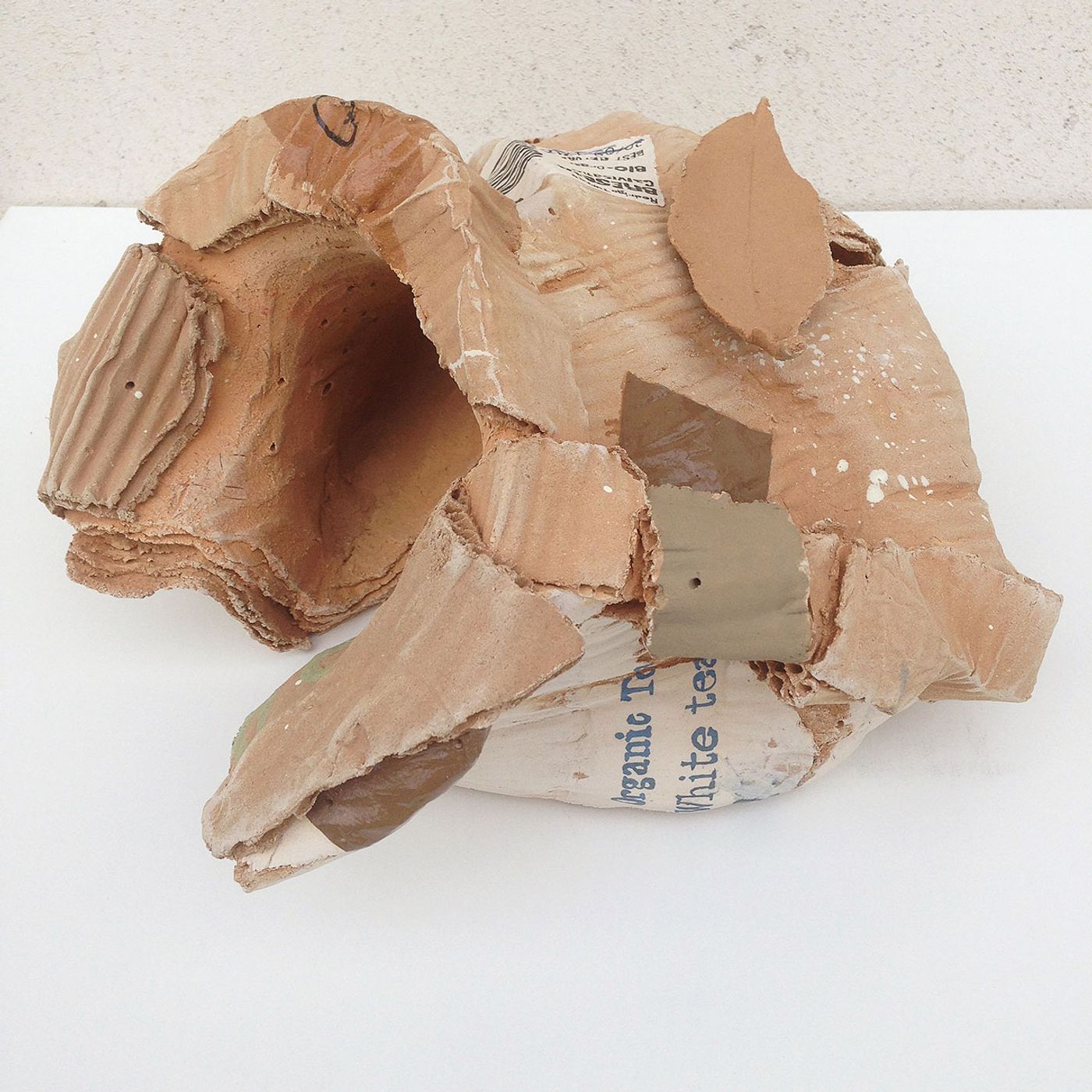

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 17.8 × 27.9 × 25.4 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over ceramic. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 17.8 x 29.7 x 29.7cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

What was your first work that made you feel confident about your direction as an artist? Did you always feel confident?

In 2001, I bought a crucifix, put two pairs of wheels on it, then painted like a race car, after that I felt like I had found something, but then, a few years later I left the religious issue behind. When I embrace an idea I always feel very confident. Of course there are ups and downs during the process, but if I see any good sign along the way, it revives me.

Your amphoras and other recent work have concealed and exposed parts, reconstructed and deconstructed parts. What does this play mean to you? Is it a commentary on preservation, on reconstruction, or something else?

I’ve been working on the idea of the fragility of human knowledge as well as the fragility of cultures. When it resides in objects that are fragile by nature, that is materials that deteriorate over the centuries and regardless of the meaning or history of each object, it all comes down to gross matter. Ceramic amphoras and vases are among the best known symbols of ancient civilizations. They were found all over the world in different periods, and are therefore one of the best representatives of human knowledge. The sheer fact that they are usually related to great ancient civilizations that disappeared under the earth makes me feel rather melancholic about the future…

Tell me about your material in some of your most well-known work: Is money beautiful?

Money is seductive. The minute drawings on them are beautifully made, all decorated, most of them are full of colors, full of pride and depict landscapes, animals, flowers, important characters, important buildings, people working, studying, dancing, playing, celebrating, there’s no sadness, no starving people, no inequality, only the bright side.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 17.8 × 27.9 × 25.4 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over ceramic. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 15 × 14 × 13 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 30 × 34 × 42 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 30 × 27 × 27 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

How is money similar to other material used in art, and how is it different?

Money is paper, but it is also a strong symbol, and that symbol is very attached to the material itself. The numbers in a bank account may be very abstract, but a banknote is touchable. When I buy banknotes to use as a material, they are different from a piece of blank paper. They come full of meanings, so I have to choose what to take from the money. With blank paper I would have to add everything.

You have said that your process is to intervene in a subject’s fabrication. What is your own objective in intervening?

When I find an opportunity to intervene in something, I feel like I’ve found a job in a company. I’m interested in how people make things, because that’s culture, that’s history. And in fitting myself somewhat in the middle of a production system, I can participate in the culture environment at a broader level -at least I feel like that.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 17.8 × 20.3 × 17.8 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 17.8 × 20.3 × 17.8 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 22.9 × 12.7 × 12.7 cm. Acrylic paint over ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 30 × 27 × 27 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 30 × 27 × 27 cm. Acrylic paint and varnish over enamelled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 82 × 38 × 38cm. Laca paint on enamelled ceramic. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

What would you say intervenes most in how you yourself are constructed as an artist? In other words, what do you think most defines your aesthetic criterion, without you having chosen it?

That’s a very difficult question to answer. It is something I want to discover and it is too early to define. Maybe 10 years from now this will be clearer. I always try to balance the original concept and the eventualities of the process, while leaving much to chance, so I never know exactly what the work is going to look like.

On his previous works

Tell me about Tromp-l’oeil. Is there a reality to art? What is that reality for you?

I think that “Tromp-l’oeil” deals with our expectations and certainties. This medium gives us something that we are acquainted with, only to destabilize us a few seconds later, showing that the world is full of surprises to be unveiled. On the other hand, many other artists are working in this direction, so if you are in the habit of regularly visiting museums, art fairs, galleries, etc, you kind of expect to be confronted with something that is not what it looks like and that creates a reality to art, that is almost predictable but no less admirable. Lastly, I’ve been trying to work with both realities, first creating objects based on the “Tromp-l’oeil” (for example the cardboard fragments made in ceramics), then I ignore the fact that it could be the work itself and use it as a part to build something else.

What sense did you want your audience to have from m2?

m2 was the most descriptive work that I have ever created; it was a criticism of real estate speculation and an attempt to reconcile artistic practice with the payment of bills. I tried to counter that speculation, by turning it into an art object and making some profit myself - in other words, I was really trying to pay the rent. However, I didn’t sell a single photo and had to pay the bills anyway.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 110 × 40 × 40cm. Aluminum, iron and enameled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, China in a Box Dynasty, 2016. 110 × 40 × 40cm. Aluminum, iron and enameled ceramics. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, Ânfora, 2017. 48.3 × 48.3 × 7.6 cm. Collage of banknotes on paper. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, Ânfora, 2017. 48.3 × 48.3 × 7.6 cm. Collage of banknotes on paper. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, Ânfora, 2017. 48.3 × 48.3 × 7.6 cm. Collage of banknotes on paper. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, Entulho, 2015. 1,5 × 8 × 0,5m. Colored pencils and pastel chalk on blasted glass. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, 2 Tempos, 2012. Variable dimensions. Acrylic paint on fire extinguisher and wall. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, The End, 2016. 40 × 40 × 8m. Collage of cells on pen and paper for passe-partout. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.

Rodrigo Torres, Tornado, 2016. 40 × 40 × 8m. Collage of cells on pen and paper for passe-partout. Photo by Rodrigo Torres. Courtesy A Gentil Carioca.